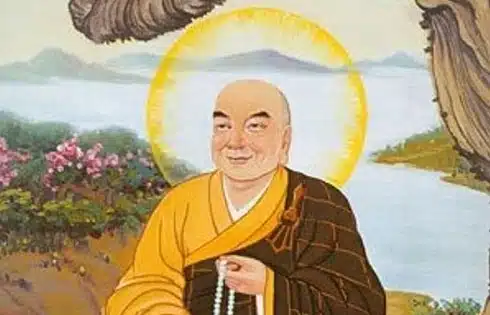

Nagarjuna is a philosopher, a sage and a true revolutionary of thought. Often hailed as the “second Buddha,” Nagarjuna is a central figure in the annals of Buddhism, leaving an indelible mark on the evolution of its philosophy.

Born in South India around the 2nd century CE, Nagarjuna led an incredible life. His intellectual prowess was apparent from an early age, and he spent his formative years delving into the profound mysteries of life and existence. This journey led him to become the founder of the Madhyamaka school of Mahāyāna Buddhism, a school that sought to navigate the “middle way” between all extremes of thought.

In this article, LotusBuddhas will introduce Nagarjuna, his profound philosophy, and his major works that have opened up a new chapter in Buddhist philosophy.

Biography – Who was Nagarjuna?

Acharya Nagarjuna was a highly esteemed Indian philosopher, and the founder of the Madhyamaka (Middle Path) school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. His profound teachings and philosophical discourses have had a significant influence on both Indian and East Asian Buddhism. While the exact dates of his life are not definitively known, it is generally accepted that Nagarjuna lived around 150-250 CE.

Nagarjuna was born into a Brahmin family in the South Indian village of Satavahana. As a young man, he converted to Buddhism and joined a monastic order, eventually becoming a highly respected monk and scholar. He is associated with the Buddhist university of Nalanda, one of the ancient world’s most significant centers of learning.

Nagarjuna is perhaps best known for his teachings on śūnyatā, or “emptiness.” According to Nagarjuna, all phenomena are devoid of inherent existence, a philosophy he expounded upon in his primary work, the “Mūlamadhyamakakārikā” (Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way). In this text, Nagarjuna utilized the concept of “dependent origination” to argue that all things exist only in relation to other things, and therefore lack any independent or inherent nature. This philosophical perspective is often referred to as “emptiness,” or “śūnyatā” in Sanskrit.

In addition to his philosophical contributions, Nagarjuna is also renowned for his contributions to the Indian tradition of alchemy. His work “Rasaratnakara,” which translates to “The Essence of Mercury,” is a significant treatise in the field of alchemy and medicine, and it provides detailed descriptions of procedures for the transmutation of base metals into gold.

Nagarjuna’s teachings have had a profound and lasting impact on the development of Mahāyāna Buddhism, particularly in East Asia, where his ideas were transmitted through texts and later adopted by various Buddhist schools, including Zen and Pure Land. His philosophy of śūnyatā has also been influential in the development of Tibetan Buddhism, where he is often revered as the “Second Buddha.”

Nagarjuna’s philosophy

Nagarjuna’s philosophy is characterized by profound insights into the nature of existence and reality. Central to Nagarjuna’s philosophy is the concept of ‘Emptiness‘ (Śūnyatā) and the doctrine of ‘two truths‘ (satyadvaya).

Nagarjuna’s interpretation of ’emptiness’ is an extension and deepening of the concept of Dependent Origination (Pratītyasamutpāda), which posits that all phenomena arise and cease due to a complex web of interdependent causes and conditions. Nagarjuna argued that because phenomena exist dependently, they lack inherent, independent existence or “svabhava”. This lack of inherent existence is what Nagarjuna referred to as ’emptiness’.

However, Nagarjuna’s concept of emptiness should not be mistaken for nihilism. His position is not that nothing exists, but rather that things do not exist in the way we typically assume – independently and permanently. Instead, phenomena exist relatively and are constantly changing due to the dynamic interplay of causes and conditions.

Complementing his exposition of emptiness is Nagarjuna’s doctrine of ‘two truths’. The ‘conventional truth’ (samvriti-satya) is the reality we experience in our everyday lives, where we operate with concepts like self and other, cause and effect. The ‘ultimate truth’ (paramartha-satya), on the other hand, is the realization of the emptiness of all phenomena, the understanding that all things lack inherent existence. Nagarjuna asserted that these two truths do not contradict each other but instead represent different levels of understanding the same reality.

Nagarjuna’s philosophy also stands out for its dialectical approach. Through the method of “tetralemma” or “catuskoti”, Nagarjuna deconstructed many metaphysical positions by demonstrating that clinging to any standpoint regarding the ultimate status of phenomena leads to logical inconsistencies.

His philosophy, thus, seeks to free our minds from entrenched views and binary thinking, opening us up to a more nuanced and flexible understanding of reality. It underscores the Middle Way, a path that steers clear of all extremes, and it lays the groundwork for a life of wisdom and compassion, central to the Buddhist path.

Major works of Nagarjuna

Acharya Nagarjuna contributed significantly to the development of Buddhist philosophy. His profound works are highly regarded in the realms of philosophy and spirituality, with his primary contributions focused on the concept of śūnyatā, or “emptiness.”

Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way): This is Nagarjuna’s magnum opus, in which he establishes the philosophy of the “Middle Way” or Madhyamaka. This text elucidates the concept of “emptiness” (śūnyatā), arguing that all phenomena are void of “svabhāva” or inherent existence or essence. This work is a critical analysis of various categories of experience and reality, leading to profound and often paradoxical conclusions about the nature of existence.

Vigrahavyāvartanī (The End of Disputes): This shorter work is a self-contained argument on the nature of perception and the problems of metaphysics. Nagarjuna addresses criticisms of the Madhyamaka viewpoint, defending the theory of emptiness against objections.

Śūnyatāsaptati (Seventy Verses on Emptiness): A verse text, this work is a further elucidation of the theory of emptiness, underscoring the central Madhyamaka doctrine that all phenomena are void of inherent existence.

Yuktisastika (Sixty Verses on Reasoning): This text emphasizes the importance of correct reasoning in understanding and practicing the Buddhist path, and it also elaborates on the concept of emptiness.

Ratnāvalī (Precious Garland): Composed as an advice to a king, this work provides ethical guidelines for rulers, presents the path to enlightenment, and explains the philosophy of the “perfection of wisdom.”

Pratītyasamutpādahṛdayakārika (Constituents of Dependent Arising): This work articulates the fundamental Buddhist doctrine of dependent origination, furthering its philosophical interpretation.

Akutobhayā (The Unceasing): This is a commentary on the Perfection of Wisdom, and is written in the form of a dialogue. It is significant for its explication of the Madhyamaka interpretation of the Perfection of Wisdom.

Bodhisambhāra (Preparation for Enlightenment): This text elucidates the practices and virtues required for attaining enlightenment.

These works, along with several others attributed to Nagarjuna, form the backbone of the Madhyamaka tradition and continue to be influential in both academic and spiritual circles. They demonstrate Nagarjuna’s acute philosophical acumen and deep understanding of Buddhist teachings. His interpretations of śūnyatā and dependent origination have been integral to the development of Mahāyāna Buddhism, profoundly influencing Buddhist thought in China, India, Tibet, Japan and Korea.

Nagarjuna as friend of Nagas

According to traditional narratives, Nagarjuna is often depicted as a “friend of the Nāgas,” a role that has both symbolic and legendary implications.

From a mythological standpoint, the stories about Nagarjuna’s relationship with the Nāgas are rich and multilayered. Perhaps the most famous narrative recounts that Nagarjuna received the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras (Heart Sutra), the seminal texts of Mahāyāna Buddhism, from the Nāgas. According to this legend, the Nāgas had been safeguarding these texts at the bottom of the ocean until a worthy recipient could be found. Nagarjuna was deemed worthy due to his deep understanding and spiritual accomplishments, and thus, the Nāgas bestowed the texts upon him. This narrative underscores Nagarjuna’s stature and role in the transmission of Mahāyāna teachings.

On a symbolic level, the title “friend of the Nāgas” also signifies Nagarjuna’s wisdom and his connection to the hidden or profound aspects of reality. In Buddhist iconography, Nāgas often symbolize the forces of the earth and the waters—elements associated with fertility, transformation and the unconscious. Hence, Nagarjuna’s association with the Nāgas suggests his ability to access and articulate profound truths, embodying the wisdom that penetrates the deepest layers of existence.

Moreover, the association between Nagarjuna and the Nāgas underscores the integral relationship between the human realm and the natural world. The Nāgas, as semi-divine beings associated with water and the underworld, represent elements of nature that are revered and respected. Nagarjuna’s friendship with the Nāgas can be seen as a metaphor for a balanced and respectful relationship with natural forces.

You can also refer to:

- Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C5%ABlamadhyamakak%C4%81rik%C4%81

- Vigrahavyāvartanī (The End of Disputes): https://www.academia.edu/33984462/The_Dispeller_of_Disuputes_N%C4%81g%C4%81rjunas_Vigrahavy%C4%81vartan%C4%AB_Translation_and_commentary_by_Jan_Westerhoff

- Madhyamaka school: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/madhyamaka/