Pure Land Buddhism, also known as the practice of Buddha-recitation, involves focusing the mind purely on remembering the names, mysterious virtues, and solemn forms of the Buddhas.

“Recitation” means to remember and contemplate, anchoring the mind on a righteous Dharma object, not wandering off into worldly thoughts, always being alert and clearly aware. Reciting the Buddha’s name involves visualizing the Buddha’s form or reciting his name, which encompasses the virtues, wisdom, and compassion of the Buddhas. By focusing on the name as the object of recitation and maintaining a pure mind as the subject, steadfastly abiding in this inherently unarising and indestructible nature, one will surely reach the realm of true peace and joy.

Practitioners who steadfastly recite the Buddha’s name or meditate on his noble form with a pure mind will generate a mysterious power, sweeping away all delusional thoughts and awakening the Amitabha nature within each sentient being. From this point, delusional thoughts are decisively eliminated, and the realm of serene and mystical tranquility will be revealed.

Throughout the vast expanse of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, notions and practices associated with these purified realms permeate various traditions. Even in Theravada Buddhism, the heavenly realm of Metteya Bodhisattva assumes a functionally equivalent role, offering a glimpse of an enlightened sphere beyond our ordinary perception.

What is Pure Land Buddhism?

Pure Land Buddhism, also known as Amidism, is a distinctive form of Buddhism that originated in India around the 2nd century CE and later flourished in East Asia, particularly China, Japan, Korea and Vietnam.

The primary focus of Pure Land Buddhism is devotion to Amitābha (also called Amitayus or Amida) Buddha, seeking rebirth in his Western Pure Land or “Sukhavati”, which is perceived as a realm free from the sufferings inherent in the cycle of rebirth, thereby facilitating the attainment of enlightenment.

The Pure Land refers to a realm of complete purity and joy without affliction or suffering, formed based on the altruistic vows of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. Through the four powers of “Loving-kindness, Compassion, Joy, and Equanimity,” combined with profound karmic connections and the fulfillment of ultimate fruition, countless Pure Lands are manifested to guide and support sentient beings in their rebirth there, where they practice until they attain Buddhahood.

Central to Pure Land Buddhism is the practice of nianfo or nembutsu (“mindfulness of the Buddha”), which involves the invocation of the name of Amitābha Buddha, often through the phrase “Namo Amituofo” in Chinese or “Namu Amida Butsu” in Japanese. This practice, which can be seen as a form of meditative concentration or prayer, is believed to engender merit and express faith in the salvific power of Amitābha Buddha, who, according to Pure Land scriptures, vowed to help all beings achieve enlightenment.

Pure Land Buddhism is predicated on the concept of Other Power (tariki), the idea that beings are saved by the compassion and vows of Amitābha Buddha, rather than their own efforts. This is contrasted with the concept of Self Power (jiriki), emphasised in many other forms of Buddhism, which asserts that enlightenment is achieved through one’s own efforts and wisdom. The faith-based nature of Pure Land Buddhism makes it an accessible and widespread form of Buddhism, appealing to a broad spectrum of individuals, regardless of their spiritual development.

The teachings of Pure Land Buddhism are primarily drawn from the Three Pure Land Sutras: the Larger Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra, the Smaller Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra, and the Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra. These texts describe Amitābha Buddha and his Pure Land, explicate the method of rebirth there, and articulate the benefits of being reborn in this celestial realm.

In East Asian countries, Pure Land Buddhism has developed unique characteristics and divergences. For instance, in Japan, two distinctive schools, Jodo Shu and Jodo Shinshu, were established by Honen (1133–1212) and Shinran (1173–1263) respectively. While both schools emphasize nembutsu, Jodo Shinshu posits that a single recitation with sincere faith is sufficient for rebirth in the Pure Land.

Overview about Amitabha Buddha

Amitabha Buddha, also known as Amida or A Di Đà, is a central figure in Pure Land Buddhism. He is considered to be a celestial Buddha, or a Buddha who has attained enlightenment and resides in a Western Paradise known as the Pure Land.

According to Pure Land teachings, Amitabha made a vow to save all beings from the cycle of birth and death and to bring them to the Pure Land. It is believed that anyone who calls upon Amitabha’s name with sincerity will be guided by him to the Pure Land at the time of death.

Amitabha is often depicted in Buddhist art as a red-colored Buddha with a crown and long flowing hair, seated on a lotus throne and surrounded by a host of Bodhisattvas. In Pure Land Buddhism, Amitabha is revered as a compassionate and merciful Buddha who is always ready to help those in need.

History of Pure Land Buddhism

The development of Pure Land Buddhism is intrinsically tied to the Mahayana sutras, particularly the three Pure Land sutras: the Larger Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra, the Smaller Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra, and the Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra. These texts, thought to have been composed between the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, expound the nature of Amitābha Buddha and his Western Pure Land, Sukhavati. While these sutras emerged in India, their influence and the subsequent development of Pure Land Buddhism were most prominent in East Asia.

Pure Land beliefs and practices first migrated to China along the Silk Road in the 2nd century CE. By the 4th century CE, Pure Land Buddhism had taken root, fostered by prominent monks such as Huiyuan, who founded the White Lotus Society, a group devoted to the recitation of the Buddha Amitābha’s name. This devotion formed the basis of nianfo practice. Over time, the Chinese interpretation of Pure Land teachings embraced an ethos of egalitarianism, positing that all individuals, regardless of social status or gender, could seek rebirth in the Pure Land.

In the Tang Dynasty (618-907), Pure Land Buddhism grew in influence, and its teachings were synthesized with those of other Buddhist schools. Most notably, the Chan (Zen) school and the Pure Land school often had overlapping practices and beliefs. Eminent monks such as Shandao played a crucial role in systematizing and popularizing Pure Land teachings during this period.

Pure Land Buddhism arrived in Japan by the 6th century CE as part of the broader transmission of Buddhism. However, it wasn’t until the Heian period (794-1185) that it became widely popular, and it reached its zenith in the Kamakura period (1185-1333). During this time, influential Japanese monks like Honen and Shinran founded the Jodo Shu and Jodo Shinshu schools, respectively. Both emphasized the nembutsu practice, although they interpreted and taught it differently.

In Jodo Shu, Honen proposed that multiple recitations of nembutsu with sincere faith led to rebirth in the Pure Land. Shinran, his disciple, took this further in the formation of Jodo Shinshu, stating that even a single, heartfelt utterance of nembutsu was enough to ensure rebirth in the Pure Land. This radical simplification appealed to the common people, leading to a widespread adoption of Pure Land practices.

In the contemporary era, Pure Land Buddhism remains one of the most practiced forms of Buddhism in East Asia, especially in Japan, China, Vietnam and Korea. It also has followers worldwide, with communities existing in the United States, Europe, and other regions outside of Asia.

Does Pure Land Really Exist?

The existence of the Pure Land, as described in Pure Land Buddhism, is a subject of extensive theological and philosophical debate, intertwined with nuanced interpretations of Buddhist cosmology, ontology, and epistemology. Given its religious nature, assertions about the existence or non-existence of the Pure Land tend to hinge on faith, personal belief, and the particular interpretation of Buddhist teachings.

The texts central to Pure Land Buddhism describe the Pure Land as a celestial realm overseen by Amitābha Buddha. According to these sutras, the Pure Land is a realm devoid of suffering and filled with various forms of aesthetic and spiritual pleasure, facilitating the attainment of enlightenment.

However, interpretations of the Pure Land’s existence vary among practitioners and scholars. For some, the Pure Land is a literal place, a distinct realm within the Buddhist cosmology. They believe that through the nianfo or nembutsu practice—reciting the name of Amitābha Buddha—individuals can be reborn into this realm and thus more easily attain enlightenment.

Others, however, interpret the Pure Land metaphorically or symbolically. In this perspective, the Pure Land represents an ideal state of mind or a manifestation of enlightenment itself. It is seen as an expression of the Buddha-nature inherent in all beings, and thus ‘rebirth’ in the Pure Land signifies a profound spiritual transformation rather than a physical relocation. The Pure Land, in this view, is intrinsically present in our reality, accessible through appropriate spiritual practice and understanding.

Some schools and thinkers combine these views, asserting that while the Pure Land may exist as a distinct realm, it is ultimately inseparable from the enlightened mind. This interpretation aligns with the Mahayana concept of nonduality, which posits that Samsara (the cycle of birth and death) and Nirvana (liberation from this cycle) are not two separate realities, but different perspectives on the same reality.

Beliefs and Core Teachings of Pure Land Buddhism

Pure Land Buddhism centers around a core set of beliefs, which, while sharing the broader Mahayana framework, imbue it with unique features and emphases.

Amitābha Buddha and the Pure Land: Central to Pure Land Buddhism is the figure of Amitābha Buddha, also known as Amitayus or Amida Buddha. Amitābha Buddha is believed to reside over the Western Pure Land or Sukhavati. This realm is depicted as a paradise free from the suffering inherent in the cycle of birth and death (samsara), thus providing an ideal environment for the pursuit of enlightenment.

Rebirth in the Pure Land: Adherents of Pure Land Buddhism aspire to be reborn in Amitābha’s Pure Land. This rebirth is not the final goal but rather a step towards the ultimate aim of Buddhahood. The Pure Land is considered a place (or state of being) where individuals can practice the Dharma without the hindrances encountered in our world, making enlightenment more attainable.

Nembutsu practice: The principal practice in Pure Land Buddhism is the recitation of Amitābha’s name, known as nianfo in Chinese or nembutsu in Japanese. This practice is seen as a means of connecting with Amitābha Buddha and expressing faith in his vows. Devotees believe that through this practice, they accumulate merit, which aids in their aspiration to be reborn in the Pure Land.

Other-power (Tariki): A distinctive belief in Pure Land Buddhism is the emphasis on Other-Power, referring to the power of Amitābha Buddha to assist beings in achieving enlightenment. This is opposed to the concept of Self-Power (jiriki) emphasized in many other Buddhist traditions, where liberation is attained primarily through one’s own efforts. This reliance on Amitābha’s power is manifest in the belief that invoking his name with faith and sincerity can secure rebirth in the Pure Land.

Universal salvation or Amitābha’s vows: Pure Land Buddhism espouses the Mahayana ideal of universal salvation, asserting that all beings can attain enlightenment and Buddhahood. The vows of Amitābha, particularly his 18th vow, pledge to ensure the rebirth in his Pure Land of all beings who recite his name with sincere faith. This teaching is seen as a manifestation of Amitābha’s boundless compassion and the fundamental Mahayana ethos of the Bodhisattva path, the aspiration to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all beings.

Accessibility of enlightenment: Pure Land Buddhism upholds the Mahayana belief that all beings possess Buddha-nature and can, therefore, attain Buddhahood. However, it also asserts that the Pure Land path to enlightenment is particularly accessible, even to those who are unable to undertake rigorous monastic practices. This democratic ethos has contributed to the broad popularity of Pure Land Buddhism.

These core teachings are interpreted and practiced in various ways across different Pure Land traditions and cultures. Nevertheless, they collectively constitute the heart of Pure Land Buddhism, elucidating its distinctive approach to the pursuit of enlightenment.

Key Practices of Pure Land Buddhism

The main practice of Pure Land Buddhism is the recitation of Amitabha Buddha’s name, known as “nembutsu.” This practice involves repeating Amitabha’s name, either silently or out loud, as a way to cultivate a connection to him and the Pure Land. By repeating Amitabha’s name, practitioners are believed to build up positive karma and purify their minds, increasing the likelihood of being reborn in the Pure Land after death.

In addition to nembutsu, other practices in Pure Land Buddhism may include:

- Meditation and visualization: While nianfo or nembutsu is the primary practice, some Pure Land schools also encourage meditation and visualization practices based on the Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra. These practices involve detailed visualizations of Amitābha Buddha and the Pure Land, fostering a deeper connection with them.

- Study of Pure Land sutras: The study of the three principal Pure Land sutras—Larger Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra, Smaller Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra, and the Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra—is considered essential. This study is a means of understanding the nature of Amitābha Buddha, his vows, and the Pure Land, providing a doctrinal foundation for the nianfo/nembutsu practice.

- Prostrations: In many Pure Land communities, devotees perform prostrations as a sign of respect and devotion towards Amitābha Buddha. This practice can be seen as a physical expression of the nianfo/nembutsu, involving the body in the act of reverence.

- Chanting of sutras: Apart from the recitation of Amitābha’s name, many Pure Land practitioners engage in the chanting of sutras, particularly the Pure Land sutras. This practice helps to instill the teachings in the mind of the practitioner and express communal devotion.

- Aspiration for birth in the Pure Land: Pure Land adherents are encouraged to cultivate a sincere aspiration to be reborn in the Pure Land. This aspiration, known as ‘raising the thought of enlightenment’ or bodhicitta in the broader Mahayana tradition, is often expressed through formal rituals and regular practice of nianfo/nembutsu.

- Merit transfer (Parināmanā): As part of the Mahayana tradition, Pure Land Buddhism upholds the practice of transferring merit. Practitioners dedicate the merit accrued from their practices to all sentient beings, expressing the Mahayana ideal of universal salvation.

It’s worth remembering that different schools of Pure Land Buddhism may have their unique practices and varying degrees of emphasis on those practices. However, by and large, the nembutsu practice is regarded as the foundation and cornerstone of the Pure Land tradition. It’s like the beating heart of the practice, driving and animating all other aspects of the path towards enlightenment.

By reciting the nembutsu and invoking the name of Amitabha Buddha with reverence and devotion, we can tap into the immense power and grace of the Pure Land and accelerate our journey towards spiritual awakening.

The Principal Pure Land Texts

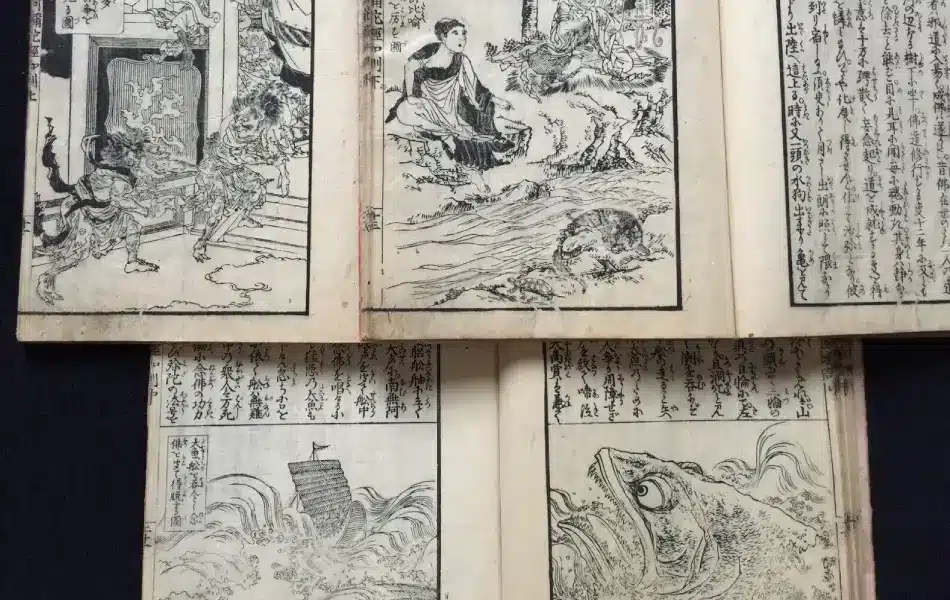

The principal texts of Pure Land Buddhism are a group of sutras that outline the nature, vows, and practices associated with Amitābha Buddha and his Pure Land, known as Sukhavati. These sutras serve as the foundational scriptures for this tradition, providing the doctrinal basis for its beliefs and practices.

Larger Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra (Infinite Life Sutra): Also known as the Larger Amitābha Sutra, this text describes the 48 vows made by Amitābha Buddha in his previous life as the bodhisattva Dharmākara. In particular, the 18th vow promises that all beings who call upon Amitābha’s name with sincere faith and aspiration will be reborn in his Pure Land. This sutra also offers a detailed description of Sukhavati, depicting it as a realm of peace, prosperity, and spiritual fulfillment.

Smaller Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra (Amitābha Sutra): This shorter sutra, also known as the Amida Sutra, focuses on the merits of faith in Amitābha Buddha and the aspiration to be reborn in his Pure Land. The text underscores the ease and efficacy of this path, portraying it as accessible even to those who can’t undertake more demanding practices. The sutra also offers a brief account of Sukhavati’s splendors, emphasizing its suitability as a realm for the pursuit of enlightenment.

Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra (Contemplation Sutra): This sutra prescribes specific meditation and visualization practices centered on Amitābha and the Pure Land. These practices aim to deepen the practitioner’s faith and connection with Amitābha, thereby facilitating their rebirth in Sukhavati. The sutra also underscores the salvific power of Amitābha’s vows, portraying them as a source of hope and comfort for all beings.

Pratyutpanna Samādhi Sūtra: Although not exclusively a Pure Land text, this sutra is significant for introducing the practice of mindfulness of Amitābha Buddha, which later evolves into the nianfo or nembutsu practice central to Pure Land Buddhism. The sutra advocates the continual recitation of Amitābha’s name as a means of attaining the Pratyutpanna Samādhi, a meditative state that enables the practitioner to perceive Amitābha and all other Buddhas directly.

In addition to these sutras, a range of commentaries and treatises by prominent Buddhist scholars have played a key role in interpreting and systematizing Pure Land teachings. Examples include Shandao’s ‘Commentary on the Contemplation Sutra’ in Chinese Buddhism and Honen’s ‘Senchaku Hongan Nembutsu Shu’ in Japanese Jodo Shu. These texts, together with the sutras, constitute the principal literature of the Pure Land tradition, shaping its doctrinal and devotional landscape over centuries.

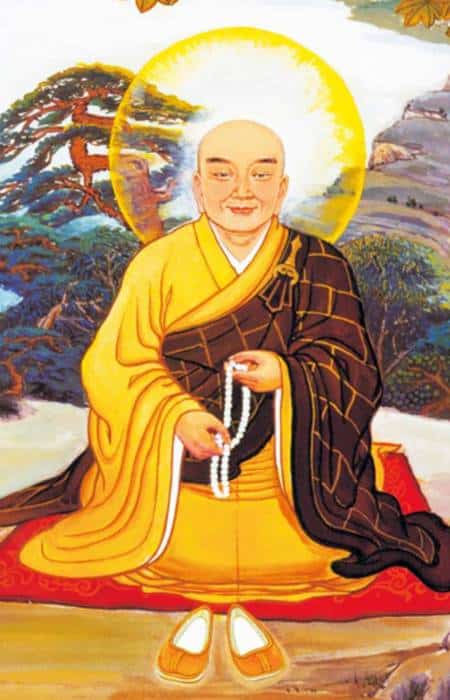

The Patriarchs of Pure Land Buddhism

The patriarchs of Pure Land Buddhism are a series of influential teachers and scholars who have significantly contributed to the development and propagation of this tradition. Often, these patriarchs are associated with specific regions, representing the evolution of Pure Land thought and practice within those cultural contexts.

Nagarjuna (2nd-3rd Century, India): While primarily known as the founder of Madhyamaka philosophy, Nagarjuna is also recognized as the first patriarch of Pure Land Buddhism. He emphasized the accessibility of Amitābha’s Pure Land and advocated practices for rebirth there, setting the stage for later Pure Land thought.

Vasubandhu (4th-5th Century, India): An eminent scholar of the Yogācāra school, Vasubandhu composed a treatise on the Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra, outlining methods of visualizing Amitābha and the Pure Land. He is regarded as the second patriarch of Pure Land Buddhism.

Tanluan (476-542, China): Tanluan is recognized as the third patriarch and the founder of Chinese Pure Land Buddhism. He emphasized faith in Amitābha and the recitation of his name (nianfo) as key to achieving rebirth in the Pure Land.

Daochuo (562-645, China): As the fourth patriarch, Daochuo further developed Pure Land teachings in China. He propounded the idea of the “Age of Mappo” or the “Degenerate Age,” arguing that in such an age, practices aimed at rebirth in the Pure Land are the most suitable path for most people.

Shandao (613-681, China): Recognized as the fifth patriarch, Shandao played a critical role in systematizing and popularizing Pure Land teachings in China. He is particularly known for his commentaries on the Contemplation Sutra and his emphasis on nianfo practice.

Honen (1133-1212, Japan): Honen is considered the founder of the Jodo Shu school in Japan and a key figure in Japanese Pure Land Buddhism. He advocated the exclusive practice of nembutsu (recitation of Amitābha’s name), arguing that it was the most effective path to enlightenment in the age of Mappo.

Shinran (1173-1263, Japan): A disciple of Honen, Shinran founded the Jodo Shinshu school. He further developed the concept of tariki, or Other Power, emphasizing reliance on Amitābha’s vow for salvation.

Rennyo (1415-1499, Japan): As the 8th Monshu (head priest) of the Jodo Shinshu Honganji tradition, Rennyo is credited with reviving and expanding the school after a period of decline.

The Difference Between Pure Land Buddhism and Other Schools of Buddhism

While there are many similarities between Pure Land Buddhism and other schools of Buddhism, such as Theravada and Mahayana, there are also some key differences.

One of the main differences between Pure Land Buddhism and other schools of Buddhism is the emphasis on “other-power” or relying on the power of Amitabha Buddha to achieve enlightenment, rather than solely on one’s own efforts. This is in contrast to the emphasis on “self-power” in other schools of Buddhism, such as Zen and Theravada Buddhism, where practitioners focus on their own efforts to achieve enlightenment through meditation and other practices.

Another difference is the emphasis on rebirth in the Pure Land as a means to achieve enlightenment, rather than the more traditional goal of achieving enlightenment in this lifetime. In Pure Land Buddhism, the practice of reciting Amitabha Buddha’s name is seen as a way to generate positive karma and create a connection with Amitabha Buddha, who will come to receive the practitioner at the time of death and guide them to the Pure Land.

Finally, Pure Land Buddhism places a strong emphasis on the importance of faith and devotion in the practice of Buddhism, which is not always as prominent in other schools of Buddhism. While other schools of Buddhism also value faith and devotion, Pure Land Buddhism places a particular emphasis on these qualities as essential for achieving rebirth in the Pure Land and ultimate enlightenment.

Overall, while there are many similarities between Pure Land Buddhism and other schools of Buddhism, such as the emphasis on compassion and wisdom, there are also some important differences in terms of the emphasis on other-power, rebirth in the Pure Land, and the importance of faith and devotion.

Reference more:

- Larger Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra (Infinite Life Sutra): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Longer_Sukh%C4%81vat%C4%ABvy%C5%ABha_S%C5%ABtra

- Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra (Contemplation Sutra): http://web.mit.edu/stclair/www/meditationsutra.html