Buddhism can be defined and explained from different perspectives as follows: Buddhism, being the doctrine of Buddha (the Enlightened One), aims to guide and develop individuals by purifying the body and mind (through the path of Morality); calming the body and mind (through the path of Meditation), and enlightening the human spirit (through the path of Wisdom).

I am Thich Tue Minh, a Buddhist monk and a member of LotusBuddhas. Twenty years ago, i was an atheist who did not believe in the supernatural doctrines of religion because there was no empirical evidence to support them, and they were blindly imposed on people. However, everything changed when a friend lent me a book on the Heart Sutra. The teachings in the sutra were like a strong slap to my foolish arrogance, and i began to delve deeper into Buddhism, realizing that it is an amazing religion.

Buddhism does not force blind faith on us but shows us the true nature of reality and the delusions of the mind that cause suffering. Each of us can verify these teachings through personal experience. Buddhism offers a practical path to peace and happiness that anyone can follow, regardless of their beliefs or background.

What is Buddhism?

General information about Buddhism:

- Origin: India.

- Time of appearance: 6th century BC.

- Founder: Shakyamuni Buddha (Prince Siddhattha Gotama) of the Sakya clan kingdom.

- Policy: Avoid doing evil things, actively do good things, cultivate pure Body, Speech and Mind.

- Form of religion: Popularity, expansion, spread through many countries around the world; belongs to atheist, does not advocate theism, does not recognize that there is a creator or god who determines the fate of human beings; belive on the Law of Cause and Effect.

- The main schools: Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism.

- Organization: The World Fellowship of Buddhists is an organization that unites all Buddhists in the world.

Buddhism is a profound and intricate religious and philosophical tradition that emerged in the 6th century BCE in present-day Nepal. It was established by Siddhartha Gautama, recognized as the Buddha or the “Enlightened One.” He aimed to address deep existential inquiries concerning the nature of human suffering, the transitory aspect of existence, and the essence of reality itself.

Contrary to being a faith system founded on supernatural edicts, Buddhism does not mandate blind faith from its adherents. Buddhists place their trust in the Buddha because he discovered the path to liberation and relief from suffering and adversity.

Buddhism serves as a methodology that assists individuals in discerning the true nature of the universe, human existence, moral integrity, and liberation. It enlightens us on how the cosmos is formed and destroyed and illustrates the existence of sentient and insentient beings. The Buddha’s teachings enable us to comprehend compassion and sanctity, while the concept of liberation provides guidance on spiritual practice for transforming the mundane into the divine.

Buddhism instructs how to attain Buddhahood, shedding suffering to achieve bliss. Misunderstandings label Buddhism as superstition, causing many to miss the opportunity to attain enlightenment and remain ensnared in the cycle of rebirth, enduring relentless suffering.

Rather than exalting a supreme supernatural entity, Buddhism advocates focusing on practical human issues, guiding how to live, balance body and mind, and foster a peaceful, joyful existence.

Buddhism emphasizes experiential and pragmatic concerns in the present over abstract, detached theories. It should not be viewed through the lens of Western religious categorizations that heavily focus on faith. Buddhist teachings are profound and practical, transcending secular sciences, philosophy, or psychology. The human quest for happiness is instinctual. However, if this quest becomes passively entangled in the realm of sensory experiences, one risks losing self-control, underscoring the necessity of mindfulness and inner governance in the pursuit of true contentment.

Gautama Buddha – Founder of Buddhism

Gautama Buddha is the founder of Buddhism. Born into the Shakya clan in the 6th century BCE in Lumbini, a region now situated in present-day Nepal, Gautama lived a sheltered early life as a prince, secluded from the harsh realities of the world outside his palace walls.

A seminal event in his life, often referred to as the “Four Sights,” occurred when Gautama ventured outside the palace and was confronted with the existential conditions of human existence – an elderly man, a sick man, a corpse and a wandering ascetic. This exposure to old age, sickness, death, and renunciation deeply disturbed him, igniting in him a profound desire to seek a solution to human suffering.

In response, at the age of 29, he renounced his princely life, including his wife and son, and embarked on a spiritual quest to understand the nature of suffering and how to eradicate it. This period involved rigorous ascetic practices and meditation. However, after recognizing the futility of extreme asceticism, he adopted a middle way between the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification.

The pivotal moment in his journey arrived when he meditated under the Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya. During this intense meditation, it is believed he attained a profound level of understanding, or “awakening” (bodhi), thereby becoming the Buddha, the “Enlightened One.” This enlightenment encompassed realization of the Four Noble Truths, which form the crux of his teachings and provide a framework to cease suffering.

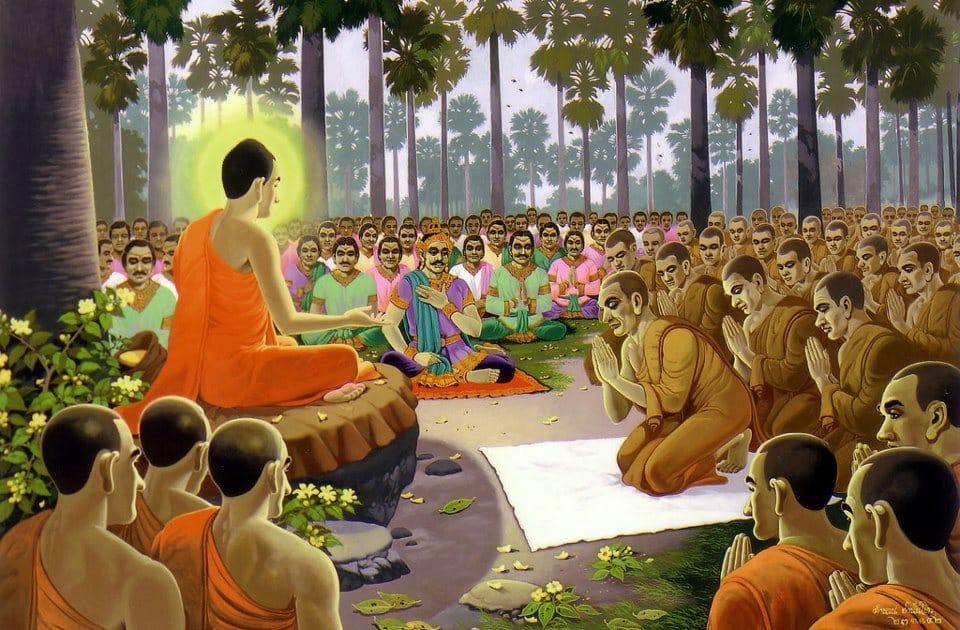

For the remaining 45 years of his life, Buddha traveled extensively, disseminating his teachings among a diverse range of people, from royalty and nobility to outcastes and criminals. His compassionate approach, intellectual rigor, and practical teachings attracted a significant following during his lifetime, laying the foundation for what would eventually become one of the world’s major religions.

Buddha passed away at the age of 80 in Kushinagar, a city in present-day Uttar Pradesh, India. His last words, “All conditioned things are impermanent. Strive on with diligence,” encapsulate the essence of his teachings: the impermanence of life and the necessity of personal effort in the pursuit of liberation and enlightenment. Despite his passing, his teachings continue to guide millions of people worldwide, making Siddhartha Gautama one of the most influential figures in human history.

History of Buddhism

The history of Buddhism traces back to the 6th century BCE in the region currently recognized as Nepal, where Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, embarked on his path towards enlightenment. Buddhism’s growth, transformation, and dispersal over centuries can be charted across three primary stages: Early Buddhism, the development of Mahayana Buddhism and the emergence of Vajrayana Buddhism.

Early Buddhism and the formation of Theravada

The earliest phase of Buddhism, often referred to as Early Buddhism, began with the Buddha’s enlightenment and his subsequent teachings. His practical teachings, known as Dharma, and the community of followers, known as Sangha, formed the two core aspects of Buddhism. After the Buddha’s death (or Parinirvana), the First Buddhist Council was convened to preserve his teachings, resulting in the compilation of the Vinaya Pitaka, rules for monastic discipline, and the Sutta Pitaka, a collection of the Buddha’s discourses.

During the Third Buddhist Council under King Ashoka’s reign in the 3rd century BCE, disputes over monastic discipline and doctrine led to the formation of distinct Buddhist schools. Ashoka, a significant figure in Buddhism’s history, embraced and promoted Buddhism across his vast Mauryan Empire, which spanned much of the Indian subcontinent. His missionary activities, including the dispatch of his son Mahinda to Sri Lanka, contributed to the spread of Buddhism beyond India.

The Theravada school, meaning “Way of the Elders,” emerged as a distinct tradition during this period, adhering closely to the early teachings of the Buddha and emphasizing individual enlightenment. Its canon, the Pali Canon or Tipitaka, is regarded as the oldest complete Buddhist canon still in existence.

Development of Mahayana Buddhism

The inception of Mahayana Buddhism, meaning “Great Vehicle,” marked a transformative phase in the history of Buddhism around the beginning of the Common Era. Originating in India, this new movement introduced novel concepts and texts, evolving into a more accessible path emphasizing the altruistic goal of becoming a Bodhisattva (a being striving for enlightenment to aid all sentient beings). The Mahayana tradition also introduced the idea of emptiness and the potentiality of Buddha-nature in all beings.

Simultaneously, the development of the Silk Road facilitated the transmission of Mahayana Buddhism to East Asia, leading to its establishment and adaptation in countries like China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. It further diversified into various schools, including Pure Land, Zen (Chan in China), Nichiren and Tiantai.

Emergence of Vajrayana Buddhism

Around the 7th century CE, a new form of Buddhism emerged, predominantly in the Himalayan regions, known as Vajrayana or Tantric Buddhism. It incorporated elements of Indian Tantra and indigenous shamanic practices, focusing on esoteric rituals, mantra recitation, visualization practices and the use of mandalas. The Vajrayana tradition, promising a swifter path to enlightenment, became firmly established in Tibet, leading to the development of Tibetan Buddhism, which continues to be practiced in Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan and Mongolia.

Buddhism in the modern era

Buddhism encountered significant challenges during the Middle Ages, especially in India, where it faced competition from a resurgent Hinduism and later from the invading Islamic rulers. By the 13th century, Buddhism had significantly declined in India but remained vibrant in other parts of Asia.

The modern era witnessed the revival and global spread of Buddhism. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Buddhist revivalist movement in countries like Sri Lanka and India, driven by figures like Anagarika Dharmapala and B.R. Ambedkar, sought to reassert Buddhist identity and principles. In particular, Ambedkar’s mass conversion of Dalits (lower caste Hindus) to Buddhism in 1956 marked a significant moment in modern Indian history.

In the late 19th century, Buddhism also began to make its way to the West through various means, such as immigration, missionary activity, and the interest of western intellectuals and artists. The World’s Parliament of Religions held in Chicago in 1893 served as a significant platform for introducing Buddhism to a broader western audience.

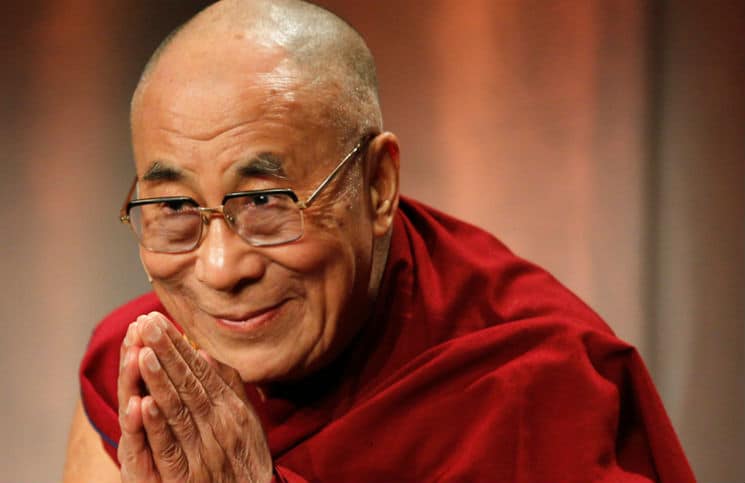

Throughout the 20th century, Buddhist principles and practices increasingly influenced western society. The transmission of Zen and Tibetan Buddhism, in particular, gained momentum with notable figures like D.T. Suzuki and the 14th Dalai Lama playing significant roles. Additionally, the integration of mindfulness and meditation practices into healthcare, education, and psychotherapy underscored Buddhism’s broad impact beyond the religious sphere.

In recent decades, the global spread and adoption of Buddhism have been facilitated by globalization and digital technology, allowing teachings and practices to be shared and accessed across different cultural and geographical contexts.

In East Asia, Buddhism continues to permeate daily life and culture, despite facing challenges during periods of modernization and political change, such as the Cultural Revolution in China. Similarly, in Southeast Asia, Theravada Buddhism remains a crucial part of individual and national identity.

On the whole, the history of Buddhism is characterized by remarkable resilience, adaptability and diversity. From its inception in ancient India, it has transformed and integrated with various cultures and societies, leading to a multitude of expressions and interpretations. As we move further into the 21st century, Buddhism continues to evolve, providing spiritual guidance and practical solutions to new generations worldwide.

Beliefs of Buddhism

Buddhism is a complex and multifaceted religious and philosophical tradition with core beliefs that are largely shared among its various branches and schools, despite the differences in practice and interpretation.

1. The Four Noble Truths

At the heart of Buddhist belief are the Four Noble Truths, which Buddha Siddhartha Gautama is said to have realized upon his enlightenment.

- The truth of dukkha: Dukkha is often translated as “suffering“, but it also encompasses unsatisfactoriness, stress and discontent. This first truth asserts that all forms of existence are characterized by dukkha.

- The truth of the origin of dukkha: The second truth identifies desire or craving (tanha) as the cause of dukkha. This includes sensual desire, desire for existence, and desire for non-existence.

- The truth of the cessation of dukkha: The third truth assures that it’s possible to end dukkha by relinquishing that very desire or craving.

- The truth of the path leading to the cessation of dukkha: The fourth truth provides a practical guideline to achieve the cessation of dukkha, known as the Noble Eightfold Path.

2. The Noble Eightfold Path

The Noble Eightfold Path prescribes a middle way of living between the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification. It can be categorized into three fundamental aspects: ethical conduct (sila), mental discipline (samadhi) and wisdom (panna).

- Right View (Understanding): Understanding the Four Noble Truths and the nature of reality, including impermanence and the principle of cause and effect (karma).

- Right Intention (Thought): Cultivating intentions of renunciation, goodwill, and harmlessness.

- Right Speech: Abstaining from lying, divisive speech, harsh words and idle chatter.

- Right Action: Abstaining from taking life, stealing and sexual misconduct.

- Right Livelihood: Earning a living in a way that does not harm others.

- Right Effort: Making a determined effort to cultivate wholesome qualities and discard unwholesome qualities.

- Right Mindfulness: Cultivating a clear awareness and attentiveness to experiences as they occur.

- Right Concentration: Developing the mental focus necessary for profound understanding.

3. Karma and Rebirth

Buddhism also asserts the principles of karma and rebirth. Karma, meaning action, refers to the law of moral causation, where every intentional action has a consequence. These consequences may manifest in this life or subsequent lives, influencing the conditions and circumstances of one’s rebirth.

Rebirth, different from reincarnation, is a process driven by the law of dependent origination, which maintains a continuity of consciousness across lives, though without an enduring self or soul (anatta).

4. Nirvana

The ultimate goal of Buddhist practice is to achieve Nirvana, often translated as “extinguishment” or “unbinding.” It refers to the cessation of the cycle of birth and death (samsara) and the extinguishing of the fires of desire, hatred and delusion. Nirvana is characterized by perfect peace, freedom and the highest form of happiness.

5. Mahayana Beliefs

In addition to these core beliefs, Mahayana Buddhism introduces the Bodhisattva ideal – a person who seeks enlightenment both for themselves and for the benefit of all sentient beings. It also emphasizes the concept of sunyata (emptiness), which suggests that all phenomena are empty of inherent existence, and the potentiality of Buddha-nature in all beings.

6. Vajrayana Beliefs

Vajrayana Buddhism, also known as Tantric Buddhism, incorporates additional beliefs and practices, including the use of mantras, mudras (symbolic hand gestures), and mandalas (symbolic representations of the universe) to expedite the path to enlightenment. Furthermore, it espouses the existence of various Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and deities, who can be invoked and meditated upon for assistance and guidance.

7. The Three Jewels

Fundamental to all branches of Buddhism is taking refuge in the Three Jewels or Triple Gem, which consist of the Buddha (the enlightened one), the Dharma (the teachings), and the Sangha (the community of practitioners). This act of taking refuge affirms a person’s commitment to the Buddhist path.

8. Dependent Origination

Another significant belief in Buddhism is the principle of dependent origination (pratityasamutpada), which holds that all phenomena arise in dependence upon other phenomena. This principle underscores the interconnectedness of all things and forms the basis of the Buddhist understanding of causality and the arising of dukkha.

9. Anatta

The doctrine of anatta or non-self, is also central to Buddhism. It proposes that there is no fixed, unchanging self or soul in living beings. This concept is closely tied to the Buddhist understanding of impermanence (anicca) and suffering.

It should be noted that while these beliefs form the core of Buddhist philosophy, their interpretations can vary significantly across different Buddhist traditions and cultures. Furthermore, while these beliefs provide a moral and philosophical framework, Buddhism also emphasizes direct experience and encourages its followers to verify the truth of the teachings through their own practice and insight. Thus, while the content of belief is important in Buddhism, equally significant is the way in which these beliefs are lived, experienced and realized.

Three Main Schools of Buddhism

Buddhism has many different schools and traditions, but there are three major branches that are recognized as the main schools of Buddhism: Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana. Here is a detailed description of each of these schools:

1. Theravada Buddhism

Theravada, often referred to as the “School of the Elders,” is the oldest surviving branch of Buddhism and is dominant in Southeast Asia, including countries such as Sri Lanka, Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar and Laos. The name “Theravada” reflects the school’s claim to adhere closely to the original teachings and practices formulated by the Buddha and his immediate disciples.

Theravada’s foundational texts are written in the Pali language and are collectively known as the Pali Canon or Tipitaka. The Tipitaka is divided into three sections: the Vinaya Pitaka (rules for monastic discipline), the Sutta Pitaka (discourses of the Buddha) and the Abhidhamma Pitaka (philosophical and psychological analysis).

Central to Theravada Buddhism is the pursuit of individual enlightenment by becoming an Arhat or a “worthy one,” an enlightened being who has eradicated all defilements. This pursuit is commonly structured around the Three Jewels (Buddha, Dharma and Sangha), the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path.

2. Mahayana Buddhism

Mahayana, meaning the “Great Vehicle,” developed out of the diverse range of Buddhist sects and schools that flourished in India during the beginning of the Common Era. Over time, it spread throughout East Asia and is now prevalent in China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam and parts of Russia.

Mahayana Buddhism introduced new sutras, doctrines, and forms of practice while maintaining the core teachings of the Buddha. It presents the Bodhisattva ideal, a person who seeks enlightenment not only for oneself but for the benefit of all sentient beings. The Mahayana perspective emphasizes compassion, wisdom and the recognition of the Buddha-nature inherent in all beings.

The texts of Mahayana Buddhism are vast and varied, including influential sutras like the Lotus Sutra, the Heart Sutra, and the Diamond Sutra. Moreover, Mahayana Buddhism has given rise to distinct philosophical schools and practices such as Pure Land, Zen, Tiantai and Nichiren Buddhism.

3. Vajrayana Buddhism

Vajrayana, or the “Diamond Vehicle,” is also known as Tantric Buddhism, largely due to its incorporation of Tantric practices and rituals. Emerging around the 7th century CE, Vajrayana Buddhism became predominant in the Himalayan regions, including Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan and Mongolia.

Vajrayana incorporates many of the sutras and teachings of the Mahayana tradition but also introduces additional texts known as Tantras. These texts detail complex ritual practices, meditation, and the use of mantras and mandalas, aiming to facilitate a rapid path to enlightenment.

One of the unique aspects of Vajrayana Buddhism is its system of recognizing and training Tulkus or reincarnated teachers, the most famous of which is the Dalai Lama of Tibet. The esoteric rituals, yogic practices, and visualizations in Vajrayana are often overseen by a spiritual mentor or guru, reflecting the importance of the guru-student relationship in this tradition.

In summary, while Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana all stem from the teachings of the historical Buddha, each school has developed unique interpretations and practices over the centuries, reflecting the diverse cultural contexts in which Buddhism has evolved.

Buddhist holidays

Buddhist holidays, like the religion itself, vary significantly across different cultures and traditions. Nonetheless, several holidays and festivals are widely observed and celebrated by Buddhists worldwide. These holidays often commemorate important events in the life of the Buddha and in the history of Buddhism.

1. Vesak (Buddha Day)

Vesak, also known as Buddha Day, is arguably the most significant holiday in the Buddhist calendar. It traditionally commemorates the birth, enlightenment and passing away of Gautama Buddha. Celebrated on the full moon day of the ancient lunar month of Vesakha (usually falls in May), the day is marked by a variety of practices such as meditation, giving to charity, and venerating the Buddha. In many countries, temples are lavishly decorated, and processions, devotional singing and storytelling events take place.

2. Magha Puja Day

Magha Puja, also known as Sangha Day, falls on the full moon day of the third lunar month (usually in February). This day commemorates a spontaneous gathering of 1,250 arahants (enlightened disciples) in the presence of the Buddha. Devotees often gather at temples for communal meditation, Dharma talks and merit-making activities.

3. Asalha Puja Day (Dhamma Day)

Asalha Puja, or Dhamma Day, is celebrated on the full moon day of the eighth lunar month (typically in July). It marks the Buddha’s first discourse, the “Turning the Wheel of Dharma” (Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta), which he gave to the five ascetics in the Deer Park at Sarnath. This event set in motion the Dharma Wheel, marking the beginning of the Buddha’s teaching career and the formation of the Sangha.

4. Uposatha Days

Uposatha days are observed on the new moon, first quarter, full moon, and last quarter of each lunar month. These days are often dedicated to intensified practice, such as extended meditation and observing additional precepts. The laity often visits local monasteries to make offerings, listen to Dharma talks and take part in communal activities.

5. Kathina Ceremony

The Kathina ceremony takes place at the end of the three-month rains retreat (Vassa), a monastic practice during the rainy season (usually from July to October). During Kathina, lay followers offer robes and other necessities to the monastic community. It’s considered a time of abundant merit-making.

6. Bodhi Day

Bodhi Day, typically celebrated in December, commemorates the day the Buddha attained enlightenment under the Bodhi tree. For many, this holiday is a time for meditation, reflection, and expressing gratitude for the teachings of the Buddha.

7. Losar (Tibetan New Year)

Losar is the Tibetan New Year and one of the most important holidays in Tibetan Buddhism. The celebration, lasting 15 days with the main festivities in the first three days, involves prayers, ceremonies, and public and private festivities.

8. Obon (Ullambana)

Obon is a Japanese Buddhist festival celebrated in July or August, dedicated to honoring and remembering deceased ancestors. It’s believed that the spirits of ancestors return during this period. The festival is marked by various customs, including ceremonial dances (Bon Odori) and the release of floating lanterns on rivers.

It is essential to note that the dates and manner of celebrating these holidays can vary significantly across different Buddhist traditions and cultures, reflecting the diversity within Buddhism. Furthermore, due to the lunisolar nature of the Buddhist calendar, the dates of these holidays may change from year to year when translated into the Gregorian calendar.

9. Pavarana Day

Pavarana Day marks the end of the Vassa retreat, often referred to as “Buddhist Lent,” a period where monks remain within their monasteries for intensive meditation and study. This period culminates in Pavarana, a day where monks can critique each other’s behavior, fostering the maintenance of the Vinaya, the monastic code. Lay followers often visit the monastery to hear Dhamma talks, participate in communal ceremonies and make offerings.

10. Anapanasati Day

Anapanasati Day is traditionally observed on the full moon of the eleventh lunar month, usually in November. This holiday commemorates a sermon given by the Buddha, in which he discussed the Anapanasati Sutta, outlining mindfulness of breathing as a meditation practice. This day is often marked by meditation retreats and Dhamma talks centered around mindfulness.

11. Hanamatsuri (Flower Festival)

Hanamatsuri, or the “Flower Festival,” is celebrated in Japan on April 8. This day celebrates the birth of Siddhartha Gautama, who would become the Buddha. The highlight of the festival is a ritual known as ‘kambutsue,’ or ‘bathing Buddha,’ where a small statue of the Buddha, representing his newborn form, is poured over with sweet tea.

12. Jodo-e (Bodhi Day or Rohatsu)

In Zen Buddhism, particularly in Japan, Bodhi Day, known as Rohatsu, is celebrated on December 8. This holiday commemorates the day the Buddha attained enlightenment under the Bodhi tree. Many Zen practitioners participate in Rohatsu sesshins, intensive meditation retreats that culminate in this celebration.

13. Parinirvana Day

Parinirvana Day, or Nirvana Day, usually observed on February 15, marks the day when the Buddha is said to have achieved complete Nirvana, upon the death of his physical body. Buddhists often meditate or reflect upon death and the transient nature of life on this day.

The diversity of festivals and observances throughout the Buddhist world reflects not only the rich cultural diversity within the tradition but also the multifaceted way in which historical events, scriptural teachings, and religious practices interplay to create living traditions.

Leader of Buddhism

Buddhism, as a widespread and diverse tradition with several branches and countless cultural adaptations, does not have a single central leader universally recognized by all Buddhists. However, numerous influential figures and leaders can be identified within different Buddhist traditions and countries.

The Dalai Lama

Perhaps the most widely recognized Buddhist leader in the world today is the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso. The Dalai Lama is the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism and traditionally the political leader of Tibet. However, the latter role has changed since the Chinese occupation of Tibet and the Dalai Lama’s exile to India in 1959. Since then, he has been a figurehead for Tibetan autonomy and has become globally recognized for his teachings on compassion, peace and interfaith dialogue.

Theravada Leaders

In Theravada Buddhism, there isn’t an equivalent singular figure like the Dalai Lama. Instead, leadership is often decentralized, with senior monks (often those who have mastered the Vinaya or monastic code) playing key roles in spiritual guidance and leadership. These individuals often lead monastic communities (sanghas) and are respected teachers or “Bhantes.” An example of such a figure is the late Ajahn Chah of Thailand, a renowned meditation teacher who influenced the development of Theravada Buddhism in the West.

Mahayana Leaders

In the Mahayana tradition, various leaders exist across different schools and sects. For example, Zen Buddhism has numerous prominent Zen masters, like the late Shunryu Suzuki Roshi in the Soto Zen tradition. In Nichiren Buddhism, Daisaku Ikeda, the president of Soka Gakkai International (a lay Buddhist organization), is a significant figure.

Sangha Leadership

The sangha, the community of ordained monks and nuns, plays a central role in all Buddhist traditions. Within a particular sangha, leadership roles are often based on seniority, with the eldest monastic (in terms of years since ordination) typically occupying a leading position. A sangha’s leadership maintains the monastic code (Vinaya), provides spiritual instruction to both monastics and lay followers, and performs religious ceremonies.

You should be noted that many Buddhist leaders, including the Dalai Lama, emphasize that the true “leader” in Buddhism is the Dharma—the teachings of the Buddha. Buddhists are encouraged to seek guidance in the Dharma and use its principles as a guide in their spiritual journey. Despite the absence of a universally recognized leader, the unity of Buddhists worldwide is maintained by shared commitment to the Three Jewels— the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha.

Main Scriptures of Buddhism

The scriptures of Buddhism, collectively known as the Buddhist canon, are the texts recognized as authentic and authoritative within different Buddhist traditions. These canons, which are composed in various languages, contain vast collections of texts that span centuries and cover a range of literary styles, philosophical discourses, and religious practices. The canons of the three main Buddhist traditions are the Tripitaka in Theravada, the Chinese Buddhist Canon and the Tibetan Buddhist Canon in Mahayana and Vajrayana respectively.

Theravada Canon (Pali Canon or Tipitaka)

The Theravada Canon, also known as the Pali Canon, is written in the Pali language. It is referred to as the Tipitaka (or “Three Baskets”) because it is divided into three main sections:

- Vinaya Pitaka: This ‘Basket of Discipline’ contains the rules for monastic conduct, procedural matters, and legal processes within the monastic community.

- Sutta Pitaka: The ‘Basket of Discourses’ comprises dialogues and discourses attributed to the Buddha and some of his closest disciples. It includes notable texts like the Dhammapada, a popular collection of the Buddha’s sayings and the Jataka tales, stories about the Buddha’s previous lives.

- Abhidhamma Pitaka: The ‘Basket of Higher Doctrine’ presents a systematic philosophical and psychological analysis of the teachings found in the Sutta Pitaka.

Mahayana Sutras

Mahayana Buddhism expanded the range of authoritative texts to include a vast corpus of Mahayana sutras, many of which are believed to be the words of the Buddha but were not included in the Tipitaka. The Mahayana sutras are written in classical Sanskrit and cover a wide range of teachings and doctrines. Notable among these are:

- The Lotus Sutra: This sutra presents the concept of the Buddha-nature and the universal potential for Buddhahood.

- The Heart Sutra and the Diamond Sutra: These form part of the Prajnaparamita Sutras, which expound on the concept of emptiness or ‘sunyata,’ a key Mahayana philosophical concept.

- The Pure Land Sutras: These discuss the nature of the Pure Land and the practices necessary to be reborn there.

Tibetan Buddhist Canon

The Tibetan Buddhist Canon is divided into the Kangyur and the Tengyur:

- Kangyur: Translated as ‘Translated Words,’ the Kangyur contains texts that are considered to be the words of the Buddha. This includes many of the Mahayana sutras, as well as texts specific to Vajrayana Buddhism, such as tantric texts.

- Tengyur: Meaning ‘Translated Treatises,’ the Tengyur contains commentaries by Indian and Tibetan scholars and practitioners on the teachings in the Kangyur.

In addition to these canons, numerous other Buddhist texts and scriptures are recognized and utilized by different Buddhist schools and traditions. These include Jodo Shinshu’s The Three Pure Land Sutras, Nichiren Buddhism’s Lotus Sutra, and Zen teachings like The Gateless Gate and The Blue Cliff Record. Furthermore, commentaries by eminent teachers, philosophical treatises, and meditation manuals also play significant roles in various traditions.

Conclusion

Buddhism is a religion for the betterment and joy of all beings, as well as for the advancement of the world. No matter where you’re from, what you’re capable of, or what your circumstances are, you’re free to apply the Buddha’s teachings and guidance to your own life.

People consider Buddhism to be a religion that emphasizes honesty and personal practice. Only individuals can practice for themselves, address their spiritual issues and suffering, and free themselves. Then, they help others follow the path of goodness, cultivating more compassion towards people in society.

Buddhists worldwide, despite their doctrinal and cultural differences, remain unified in their refuge in the Three Jewels—the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha—and their commitment to the core principles of wisdom, ethical conduct, and mental cultivation. In its enduring relevance, Buddhism continues to inspire individuals on the path to spiritual awakening and contribute to dialogues on ethics, peace and interfaith understanding in the contemporary world.