During its formation and development, Buddhism was transmitted from India to neighboring countries, to East Asia, and then spread worldwide. This development is divided into two directions: northward, known as Mahayana Buddhism, which carries the Mahayana thought, and southward, known as Theravada Buddhism, embodying the Hinayana thought.

The Mahayana (Great Vehicle) sect, meaning “great rescue path” or “great vehicle,” is considered a reformed religion. Mahayana teachings introduce many innovations compared to original Buddhism. This sect believes that not only monks but also lay Buddhists can be saved.

Therefore, Mahayana Buddhism advocates not only self-liberation and enlightenment but also helping others achieve the same. Mahayana holds that anyone can reach Nirvana through their efforts and promotes mass liberation.

Mahayana Buddhism perceives the cycle of life and death and Nirvana not as separate realms but as integrated aspects of existence. One can attain Nirvana during the cycle of life and death itself.

What is Mahayana Buddhism?

Mahayana Buddhism, one of the two principal Buddhist traditions alongside Theravada, plays a significant role in the religious landscape of northern Asia. Mahayana Buddhism is popular in countries such as China, Japan, Vietnam, South Korea and North Korea.

Deriving its name from the Sanskrit words ‘maha,’ signifying ‘great,’ and ‘yana,’ referring to ‘vehicle’. Hence, Mahayana Buddhism is called “Great Vehicle” or “Northern Buddhism”. As the largest branch of Buddhism, it incorporates Yogachara, a philosophical school intimately connected with yoga practice.

The Mahayana tradition is characterized by its diversity, being divided into four practice-oriented schools: Zen, Pure Land, Vajrayana, and Vinaya, and four philosophy-grounded schools: Yogachara, Tendai, Avamtasaka, and Madhyamika. While some scholars propose recognizing Vajrayana as an independent tradition, thus making it the third principal branch of Buddhism, it generally remains categorized within the Mahayana framework.

Contrary to the Theravada tradition, where the ultimate goal lies in becoming an enlightened saint or arahant who attains nirvana, the Mahayana path encourages adherents to aspire to become bodhisattvas. These enlightened beings, distinguished by their altruistic commitment, choose to delay their own nirvana in order to aid others in achieving this enlightened state.

This unique perspective of the Mahayana tradition extends the possibility of enlightenment to laypeople, not just monastic practitioners, asserting that enlightenment can be achieved within a single lifetime. However, the various schools within the Mahayana tradition differ on the precise methods for achieving this end.

History of Mahayana Buddhism

Mahayana Buddhism, one of the most prominent forms of Buddhism, possesses a rich and complex history dating back to the 1st century CE. Emerging out of India, this ‘Great Vehicle’ tradition represented an evolution in Buddhist thought and practice, distinguished from the earlier, more conservative Theravada tradition.

The origins of Mahayana Buddhism are somewhat shrouded in mystery due to a lack of comprehensive historical records. However, it is generally agreed that it emerged as a distinct movement during the beginning of the Common Era in India. Its formation represents a response to the perceived limitations of the earlier Theravada tradition, with a particular emphasis on the accessibility of enlightenment and the bodhisattva ideal.

Mahayana Buddhism was a diverse and expansive movement from the onset, encompassing a wide array of scriptures, teachings, and practices. It introduced a multitude of new sutras, known as the Mahayana sutras, that had not been part of the earlier canons. These texts, believed to be the word of the Buddha, became the foundation of Mahayana thought and practice. Among them were influential texts such as the Lotus Sutra, the Heart Sutra and the Diamond Sutra.

The early Mahayana tradition was influenced by a number of philosophical and religious movements in India, including the Madhyamaka school of Buddhist philosophy, which emphasized the emptiness or lack of inherent existence of all phenomena, and the Yogacara school, which taught that ultimate reality is a kind of consciousness or awareness.

Over the centuries, Mahayana Buddhism spread across Asia, largely due to the efforts of merchants and monks along the Silk Road, a network of trade routes linking China with the West. As it spread, it evolved into several distinct schools of thought, including Zen, Pure Land, Vajrayana, and others. These schools represented different interpretations and practices within the broad Mahayana tradition.

By the 6th century, Mahayana Buddhism had become the dominant form of Buddhism in China. From China, it spread to Korea and Japan, where it further diversified and evolved. The Pure Land school, emphasizing faith and devotion, and the Zen school, emphasizing meditation and mindfulness, were particularly influential in these regions.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Mahayana Buddhism began to take root in the Western world, particularly in the United States. This was primarily due to immigration from East Asia and growing interest in Buddhist philosophy and meditation. Today, Mahayana remains one of the most practiced forms of Buddhism worldwide, continuing to evolve and adapt to contemporary needs and cultures.

The Language used in Mahayana Buddhism

Mahayana Buddhism has historically used a variety of languages, depending on the region and time period. The earliest Mahayana texts were written in Sanskrit, which was the literary and religious language of ancient India.

Sanskrit continued to be the primary language of Mahayana Buddhism for several centuries, and many important Mahayana texts, including the Prajnaparamita Sutras and the Lotus Sutra, were composed in Sanskrit.

As Mahayana Buddhism spread to other parts of Asia, it was translated into a variety of local languages, including Chinese, Tibetan, Korean, and Japanese. In China, Mahayana Buddhism was first translated into Chinese during the Han dynasty, and this led to the development of a distinctive Chinese Buddhist vocabulary and literary style. In Tibet, Mahayana Buddhism was translated into Tibetan beginning in the 7th century, and this led to the development of a rich tradition of Tibetan Buddhist literature and scholarship.

In Japan, Mahayana Buddhism was initially transmitted orally and was later recorded in Japanese using a mixture of Chinese characters and indigenous phonetic scripts. This led to the development of a unique form of Japanese Buddhist literature, including works such as the Shobogenzo by the Zen master Dogen and the writings of the Pure Land master Shinran.

Today, Mahayana Buddhism continues to be practiced in a variety of languages around the world, and there is also a growing body of literature and scholarship in English and other Western languages.

Who does Mahayana Buddhism Worship?

Mahayana Buddhism extends its reverence beyond Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha, embracing a multitude of other enlightened figures as objects of worship.

This branch of Buddhism recognizes an array of Buddhas such as Amitabha, Maitreya, and the Medicine Buddha, underscoring a universal potential for enlightenment. Mahayana posits that enlightenment is accessible to all, evidenced by revered figures like Manjushri, Avalokiteshvara (Guanyin), and Samantabhadra who have attained Buddhahood.

In Mahayana temples, visitors can observe an array of Buddha statues, each embodying different qualities and teachings. These temples also honor Bodhisattvas—enlightened beings who, out of compassion, forgo final nirvana to aid others on their spiritual journeys.

Avalokiteshvara, known for his infinite compassion, stands out as one of the most venerated Bodhisattvas, symbolizing the embodiment of mercy and kindness. Through these practices, Mahayana Buddhism fosters a community centered on compassion, wisdom, and the pursuit of enlightenment for the benefit of all beings.

Beliefs of Mahayana Buddhism

A central belief in Mahayana Buddhism is the bodhisattva ideal. Unlike Theravada Buddhism, where the ultimate goal is to become an arahant or enlightened saint who attains nirvana, Mahayana Buddhists aspire to become bodhisattvas. These are compassionate beings who have achieved enlightenment but choose to delay their own nirvana to assist others on the path. This commitment to altruistic action for the benefit of all sentient beings embodies the essence of the bodhisattva ideal.

Another key belief of Mahayana Buddhism is the universality of Buddha-nature. Mahayana teachings assert that all beings possess the inherent potential for enlightenment, often termed as ‘Buddha nature’. This perspective extends the possibility of enlightenment beyond the monastic community to all individuals, regardless of their lay or monastic status.

The doctrine of emptiness, or ‘shunyata’, also plays a pivotal role in Mahayana belief. Emptiness in this context does not denote ‘nothingness’, but rather the interdependent nature of all phenomena. This principle encourages practitioners to see beyond surface appearances to understand the interconnected nature of existence.

The Mahayana tradition also acknowledges a cosmology replete with numerous Buddhas and bodhisattvas, transcending the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni. These celestial beings are often the focus of devotion and are believed to inhabit numerous ‘Buddha-lands’ across the universe.

While these are core beliefs within Mahayana Buddhism, it is vital to note that the tradition encompasses a variety of schools, each with its unique interpretations and practices. For instance, Pure Land Buddhism places strong emphasis on faith in Amitabha Buddha, while Zen Buddhism stresses the importance of meditation and direct experience. Despite these variations, all schools of Mahayana Buddhism share a commitment to the ideals of compassion, wisdom and liberation for all beings.

Core Teachings of Mahayana Buddhism

Mahayana Buddhism is characterized by a wide range of teachings and practices, but there are several core teachings that are central to the Mahayana tradition. These include:

The Bodhisattva Ideal: The Bodhisattva Ideal is the central ethical and spiritual aspiration of Mahayana Buddhism. A bodhisattva is a being who has attained enlightenment, but who chooses to remain in the cycle of birth and death (samsara) in order to help others attain enlightenment as well. The bodhisattva ideal is based on the cultivation of compassion, wisdom, and skillful means, and it emphasizes the importance of serving others and working for the benefit of all beings.

Bodhicitta: Bidhicitta is the intention or aspiration to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings. It is considered the foundation of the Mahayana path and is cultivated through the practice of meditation, ethical conduct, and the development of wisdom and compassion. Bodhicitta is seen as the motivating force behind the bodhisattva’s activities and is an essential aspect of the Mahayana Buddhist path.

Emptiness: Emptiness is a core philosophical concept in Mahayana Buddhism. It refers to the idea that all phenomena lack inherent existence or self-nature, and that their existence depends on causes and conditions. Emptiness is not a nihilistic or relativistic view, but rather a way of understanding the interdependence and interconnectedness of all things. It is closely related to the Buddhist concept of dependent origination, which teaches that all things arise in dependence on other things.

The Six Perfections: The Six Perfections (paramitas) are a set of ethical and spiritual practices that are central to the path of the bodhisattva. They include generosity, ethics, patience, perseverance, concentration, and wisdom. The Six Perfections are seen as essential for cultivating the qualities of a bodhisattva and progressing on the path toward enlightenment.

Buddha nature: Buddha Nature is the innate potential for enlightenment that is said to exist within all beings. It is the fundamental nature of mind, and it is not something that can be created or destroyed. The Buddha Nature is seen as the basis for the bodhisattva ideal, and it is the ultimate source of wisdom and compassion.

The Two Truths: The Two Truths refer to the distinction between conventional truth (samvriti-satya) and ultimate truth (paramartha-satya). Conventional truth refers to the relative reality of everyday experience, while ultimate truth refers to the ultimate nature of reality, which is characterized by emptiness. The Two Truths are not seen as contradictory, but rather as complementary ways of understanding reality. Understanding the Two Truths is an important aspect of Mahayana Buddhist philosophy and practice.

The Three Bodies of the Buddha: The Three Bodies of the Buddha (trikaya) are a way of understanding the nature of the Buddha. They include the Dharmakaya (the body of truth), the Sambhogakaya (the body of bliss), and the Nirmanakaya (the body of manifestation). The Three Bodies of the Buddha are seen as interdependent and interconnected, and they represent different aspects of the Buddha’s enlightened nature.

So, these main teachings of Mahayana Buddhism are totally connected and have each other’s backs, you know what I’m saying? And they give us a way to understand how to become a bodhisattva and what the ultimate goal of all this is: getting enlightened for the sake of every living being. It’s like a roadmap, a guidebook to help us get there.

The Difference Between Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism

Mahayana Buddhism and Theravada Buddhism are two major branches of Buddhism, with some key differences:

Goal: The goal of Theravada Buddhism is to achieve individual liberation from suffering and reach the state of Arahant, while the goal of Mahayana Buddhism is to attain Buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings.

Bodhisattva path: Mahayana Buddhism places a greater emphasis on the bodhisattva path, which involves cultivating compassion for all sentient beings and working for their benefit. Theravada Buddhism does not emphasize the bodhisattva path as much.

Scriptures: Theravada Buddhism relies mainly on the Pali Canon, while Mahayana Buddhism includes a wider range of sutras and texts.

Role of the Buddha: In Theravada Buddhism, the Buddha is seen as a teacher who has achieved individual liberation. In Mahayana Buddhism, the Buddha is seen as an ideal and a source of inspiration for the bodhisattva path.

Practices: While both branches emphasize meditation, Mahayana Buddhism places more emphasis on practices such as mantra recitation, deity yoga, and visualization.

Emptiness: While both branches of Buddhism emphasize the concept of non-self, Mahayana Buddhism places a greater emphasis on it, and developed the concept of “sunyata” which emphasizes the ultimate nature of emptiness.

Iconography: Mahayana Buddhism developed an elaborate iconography of bodhisattvas and other deities, while Theravada Buddhism does not place as much emphasis on the use of imagery and symbolism.

Geography: Theravada Buddhism is mainly practiced in Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka, and parts of India, while Mahayana Buddhism is practiced in East Asia, including China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and Tibet.

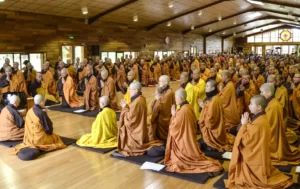

Monasticism: Monasticism is an important part of both branches of Buddhism, but in Theravada Buddhism, the monastic community is seen as the primary means of preserving and transmitting the dharma, while in Mahayana Buddhism, lay practitioners also play a significant role in the propagation of the dharma.

Even though there are some differences, both types of Buddhism are actually pretty similar, you know? They’re both trying to achieve the same thing: getting rid of suffering. They both think that being a good person, meditating, and gaining wisdom are key to reaching that goal.

Major Schools of Mahayana Buddhism

Mahayana Buddhism is characterized by a remarkable diversity of thought and practice. This multifaceted tradition has given rise to several prominent schools, each with its distinct interpretations and emphasis within the Mahayana framework. Here, we focus on four of the most influential schools: Zen, Pure Land, Vajrayana, and Yogachara.

- Zen Buddhism: Emerging in China and later spreading to countries like Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, Zen Buddhism emphasizes direct insight into one’s Buddha nature through meditation (Zazen) and mindfulness in daily life. This school is known for its simplicity, directness, and focus on experiential wisdom rather than textual learning. Zen practitioners often employ koans (paradoxical questions or statements) as a means to transcend rational thought and facilitate spiritual awakening.

- Pure Land Buddhism: As one of the most popular schools of Mahayana Buddhism, Pure Land emphasizes faith and devotion to Amitabha Buddha, known as the Buddha of Infinite Light and Life. Practitioners aspire to be reborn in Amitabha’s Western Pure Land, a realm free from the suffering of samsara, where they can more easily attain enlightenment. Recitation of the name of Amitabha Buddha (Nembutsu) is a central practice in this school.

- Vajrayana (Tantric Buddhism): While some scholars categorize Vajrayana as a separate tradition, it can also be seen as a school of Mahayana Buddhism. Prominent in Tibet and Mongolia, Vajrayana incorporates esoteric practices such as mantra recitation, deity yoga, and elaborate rituals. It also introduces the concept of the guru or spiritual teacher as a vital guide on the path to enlightenment.

- Nichiren Buddhism: Named after its founder, the 13th-century Japanese monk Nichiren, this school places exclusive emphasis on the Lotus Sutra, asserting that it contains the ultimate truths of Buddhism. Nichiren Buddhism encourages its practitioners to chant the phrase “Nam-myoho-renge-kyo” (Devotion to the Mystic Law of the Lotus Sutra) to bring forth the buddha nature in one’s own life and achieve enlightenment.

- Yogachara: Also known as ‘Consciousness-Only’ or ‘Mind-Only’ School, Yogachara proposes that our experiences of reality are projections of our own mind. It presents a detailed analysis of mind and consciousness, positing that understanding our own mental processes is key to achieving liberation. While not as popular today as Zen and Pure Land, Yogachara’s teachings have deeply influenced other Mahayana schools and philosophies.

Each of these schools, while sharing the broader Mahayana commitment to the bodhisattva path and universal enlightenment, contributes unique practices and perspectives to the tradition’s rich tapestry. Through their individual approaches, they offer practitioners varied paths towards the shared goal of liberation from suffering and ultimate enlightenment.

The Development of Mahayana Buddhism in Europe and America

The development of Mahayana Buddhism in Europe and the United States represents a noteworthy chapter in the global expansion of Buddhism. This dissemination outside of its traditional Asian contexts has been facilitated by both immigration and the growing Western interest in Buddhist philosophy and practice.

The initial introduction of Mahayana Buddhism to the West can be traced back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, largely driven by intellectual curiosity and philosophical exploration. Early translations of Buddhist texts, along with the works of scholars and philosophers like D.T. Suzuki and Alan Watts, played a key role in raising awareness and interest in Mahayana philosophies, particularly Zen Buddhism.

In the United States, the significant influx of Chinese and Japanese immigrants in the 19th century marked the beginning of established Buddhist communities. Temples were built to cater to these communities, many of which adhered to Mahayana traditions such as Pure Land and Zen. Over time, these traditions began to attract interest from the broader American population, leading to the development of convert Buddhist communities.

The latter half of the 20th century saw a proliferation of Zen centers and Tibetan Buddhist groups in both Europe and the United States, sparked in part by the arrival of Asian teachers and the interest of Western seekers. Figures like Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, founder of the San Francisco Zen Center, and Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, who established Naropa University and Shambhala International, were instrumental in making Zen and Tibetan Buddhism, respectively, accessible to Western audiences.

As Mahayana Buddhism took root in the West, it adapted to its new cultural contexts. It engaged with issues such as gender equality, environmentalism, and social justice, which led to the evolution of a distinctly Western form of Buddhism that blends traditional teachings with contemporary concerns.

Today, Mahayana Buddhism continues to flourish in Europe and the United States, demonstrating a remarkable capacity to adapt and evolve. Through this ongoing process of transformation, Mahayana Buddhism has become a significant part of the religious and philosophical landscape in the West, influencing the lives of millions and contributing to the rich diversity of spiritual practices.