Theravada Buddhism preserves accurately what Lord Buddha Gotama taught, without distortion, respecting and maintaining the original teachings (Dhamma) of Him.

Theravada Buddhism is a tradition where the Great Elders strive to preserve and maintain the original, pure, and complete Dharma, which Lord Buddha Gotama directed over 2600 years ago; studying, teaching, and practicing the Dharma based on the Pali Canon Tripitaka & Pali Commentaries compiled by the Great Elders, encapsulating Lord Buddha’s teachings transmitted to this day, including the Vinaya Pitaka, Sutta Pitaka & Abhidhamma (Higher Dharma), along with the Commentaries; additionally, there are Sub-commentaries and further reference materials.

What is Theravada Buddhism?

Originating in the historical expanse of India, Theravada Buddhism sets itself apart as a unique branch of Buddhism that strictly adheres to the original teachings of Gautama Buddha. It significantly distinguishes itself from various other Buddhist schools that juxtapose Buddha’s doctrines with the philosophies of other eminent Buddhist figures. Theravada Buddhism carves its position as a singular entity within the spectrum of hundreds of diverse Buddhist practices.

As Buddhism continued to spread throughout India after the Buddha’s Parinirvana, various interpretations of the original teachings emerged, leading to divisions within the monastic community and the rise of up to 18 different Buddhist sects.

One of these sects eventually initiated a reform movement and self-identified as Mahayana (Greater Vehicle). This led to the diminishing of another sect, considered less significant, known as Hinayana (Lesser Vehicle), which we refer to as Theravada Buddhism today as the sole surviving school of these ancient non-Mahayana traditions.

To avoid the disrespectful connotations of using the terms Hinayana and Mahayana, more neutral language is now employed to refer to these two main branches of Buddhism. Since Theravada historically dominated Southern Asia, it is often called Southern Buddhism, while Mahayana, which spread north from India to China, Tibet, and Korea, is referred to as Northern Buddhism.

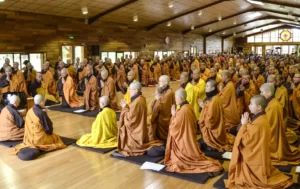

Critical aspects of Theravada Buddhism are steeped in ritualistic and contemplative practices such as sutra chanting and meditation, along with sacrificial offerings within designated temples. These practices embody the spiritual and philosophical underpinnings of this sect.

A salient belief within Theravada Buddhism asserts the notion that the attainment of Nirvana, a state symbolizing perfect enlightenment, is immediately accessible only to monks. Conversely, laypeople, whilst remaining integral to the community, are understood to have the potential to cultivate karmic merit, enabling a more advantageous rebirth in the succeeding life. This dichotomy underscores the path of spiritual progression within the Theravada Buddhist tradition.

History of Theravada Buddhism

Theravada Buddhism, also known as the “Doctrine of the Elders,” is the oldest and most orthodox form of Buddhism. It traces its origins back to the teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha in the 5th century BC and the subsequent codification of his teachings in the Pali Canon, the authoritative scripture of Theravada Buddhism.

The period of Theravada Buddhism refers to the doctrines that were transmitted directly from the time of the Buddha’s enlightenment and were passed down for about three to four generations until after his Parinirvana, a time when the internal Buddhist community had not yet differentiated, and the ideology remained unified.

The timeline can be calculated as follows: If the Buddha passed away in 486 BCE and he lived to be 80 years old, then he was born in 565 BCE. He attained enlightenment at the age of 30, which would be in 530 BCE. Buddhism divided into different sects about 100 years after the Buddha’s Parinirvana. Therefore, we can determine the timeframe of the first period to be from 530 BCE to 370 BCE.

In the centuries following the death of Gautama Buddha, various Buddhist schools emerged, each with its own interpretation of the Buddha’s teachings. At the First Buddhist Council, convened shortly after the Buddha’s death, his teachings were systematically recorded by his direct disciples. Over the next few centuries, significant philosophical differences led to the Second and Third Buddhist Councils, resulting in the establishment of distinct schools of Buddhism.

Theravada emerged as a distinct school during the Third Buddhist Council under the reign of Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BC. This council sought to purge the monastic community of monks who had strayed from the Buddha’s original teachings. The Theravada school, focusing on maintaining the original teachings as they believed it was taught by the Buddha, migrated to Sri Lanka under the guidance of Mahinda, Ashoka’s son, marking the start of Theravada Buddhism’s international journey.

In Sri Lanka, Theravada Buddhism flourished and played a significant role in shaping the island’s cultural and political landscape. The Fourth Buddhist Council, held in Sri Lanka, saw the writing of the Pali Canon onto palm leaves, ensuring the preservation of Theravada scriptures for future generations.

From Sri Lanka, Theravada Buddhism spread throughout Southeast Asia. By the 13th century AD, it had become the dominant form of Buddhism in Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and parts of Vietnam and Malaysia. Each of these cultures incorporated Theravada Buddhism into their societies, which in turn impacted their traditions, laws, and daily lives.

Throughout its history, Theravada Buddhism has maintained a strong emphasis on monastic life (Sangha), the study and meditation on the Pali Canon, and the attainment of personal liberation through the Noble Eightfold Path. It is often seen as a conservative form of Buddhism because it seeks to preserve the original teachings of the Buddha.

In the late 19th and 20th centuries, Theravada Buddhism began to interact more directly with the Western world, thanks to colonialism and globalization. This led to the formation of Theravada communities in Europe, North America, and Australia, introducing Western audiences to Buddhist philosophy and practices.

Today, Theravada Buddhism continues to play a pivotal role in Southeast Asia’s socio-cultural fabric while also gaining followers around the world. As a school of thought, it remains committed to the path of self-liberation through insight and mindfulness, as taught by Gautama Buddha over two millennia ago.

The Language Used in Theravada Buddhism

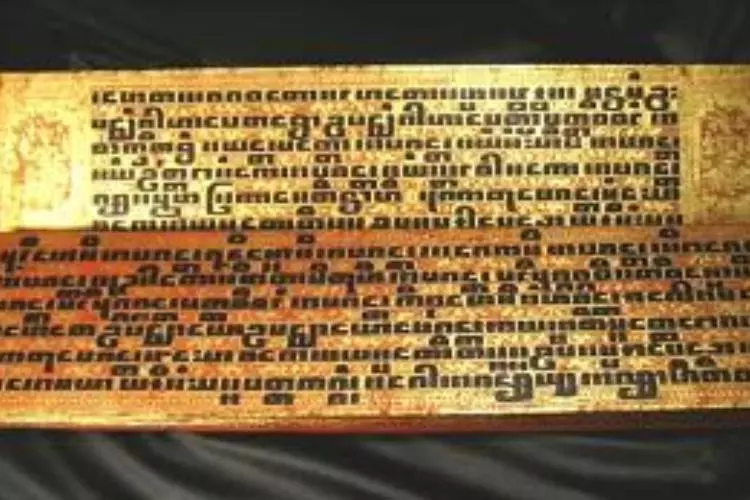

The primary language used in Theravada Buddhism is Pali, which is an ancient Indian language closely related to Sanskrit. It is the language in which the Tipitaka, the sacred scriptures of Theravada Buddhism, was written down.

During the Buddha’s time, most of his sermons were memorized by Ananda. Immediately after the Buddha’s death around 480 BC, the community of monks and Ananda were assembled to recite all the teachings they had heard during the 45 years following the Buddha’s enlightenment.

Each lesson (sutta) began with the sentence, “Evam me sutam” – “I have heard so”. The teachings were transmitted orally within the Sangha community for hundreds of years until the birth of the Tripitaka. Pali was originally a spoken language, so it did not have its own alphabet. It was not until around 100 BC that the Tripitaka was first written down by monks in Sri Lanka who used the Pali font in the form of the Brahmi script.

Since then, the Tripitaka has been translated into many other languages, including Devanagari, Thai, Burmese, Roman, Cyrillic, and more. Although English translations of the Tripitaka are popular today, many Theravada Buddhist monks still learn Pali to deepen their understanding and accurate appreciation of the Buddha’s teachings.

The exact authenticity of the Tripitaka cannot be proven, unlike the scriptural texts of many other world religions that are acknowledged as a truth, revealed by a prophet, and fully accepted by faith.

Instead, the doctrines of the Pali Canon must be evaluated directly through each individual’s experience, so that they can find the most accurate answer for themselves. To this day, the Pali Canon has survived for centuries as an indispensable guide for millions of Buddhists in their quest for enlightenment.

Beliefs of Theravada Buddhism

At its core, Theravada Buddhism is founded on the Four Noble Truths, the doctrine that Buddha Gautama is believed to have realized upon achieving enlightenment:

- Dukkha (Suffering): This truth acknowledges that life is marked by suffering, dissatisfaction, and impermanence. It encompasses everything from the subtleties of dissatisfaction to the most severe forms of physical and mental pain.

- Samudaya (Cause of Suffering): This truth states that the root cause of suffering is tanha, or desire, which can be further classified into sensual, existential, and ignorance-based desires. It is the thirst for clinging to pleasurable experiences, existing perpetually, or not understanding the true nature of reality.

- Nirodha (Cessation of Suffering): This truth explains that it is possible to end suffering by extinguishing its causes, leading to a state of ultimate peace known as Nibbana (or Nirvana).

- Magga (Path to Cessation of Suffering): This truth lays out the path leading to the end of suffering, known as the Eightfold Path. This comprises right understanding, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration.

Theravada Buddhism places a significant emphasis on the Sangha or monastic community. Monks and nuns renounce worldly life and commitments, dedicating themselves entirely to the pursuit of enlightenment. They follow the Vinaya Pitaka, a portion of the Pali Canon that outlines monastic rules and discipline.

Central to Theravada belief is the concept of ‘Anatta’ or ‘non-self’. It posits that there is no enduring, unchanging self or soul, rejecting the concept of a permanent identity. It implies that all phenomena, including the self, are impermanent, subject to change, and devoid of a static essence.

In line with this, Theravada Buddhism also highlights the concept of ‘Anicca’ or ‘impermanence’, teaching that all conditioned phenomena are transient, and ‘Dukkha,’ suffering or unsatisfactoriness, is inherent in life.

Theravada Buddhists also believe in Karma, suggesting that intentional actions have corresponding positive or negative consequences. Actions performed in this life can bear fruit in this life or the next, contributing to the cycle of birth, death and rebirth (Samsara).

However, the ultimate goal in Theravada Buddhism is achieving Nibbana, a state beyond suffering and the cycles of rebirth, marking the end of Samsara. This state is achieved by following the Noble Eightfold Path, cultivating moral virtue (sila), mindfulness and meditation (samadhi), and wisdom (panna).

It’s worth noting that while Theravada Buddhism encourages individual pursuit of enlightenment, it also values and promotes compassion, loving-kindness, and generosity towards others. Despite its emphasis on monastic life, lay followers are a vital part of the community, supporting the Sangha and practicing ethical conduct, generosity and mindfulness in their daily lives.

Core Teachings of Theravada Buddhism

The core teachings of Theravada Buddhism revolve around the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Eightfold Path, and central concepts such as Anatta (non-self), Anicca (impermanence), and Dukkha (suffering).

- Four Noble Truths: These truths are the cornerstone of the Buddha’s teaching. They are:

- Dukkha: Life is permeated with suffering, dissatisfaction, and impermanence.

- Samudaya: The origin of this suffering lies in desire or craving (tanha), which is rooted in ignorance of the true nature of reality.

- Nirodha: The cessation of suffering is possible by eliminating desire.

- Magga: The way to eliminate desire and thus suffering is by following the Noble Eightfold Path.

- Noble Eightfold Path: This path constitutes a set of guidelines for ethical living and spiritual growth. The path is divided into three categories, namely wisdom (panna), ethical conduct (sila), and concentration (samadhi). It includes:

- Wisdom: Right understanding and right thought.

- Ethical Conduct: Right speech, right action, and right livelihood.

- Concentration: Right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration.

- Anatta (Non-self): One of the key distinguishing features of Buddhism, including Theravada Buddhism, is the concept of Anatta, which negates the existence of a permanent, unchanging self or soul. This is contrary to many other religious traditions that believe in an eternal soul. The concept of Anatta asserts that the perception of self is an illusion arising from the aggregation of the Five Aggregates: form, sensation, perception, mental formations, and consciousness.

- Anicca (Impermanence): Anicca is the understanding that all phenomena, whether physical or mental, are impermanent and subject to change. Nothing in the world is permanent, and clinging to the notion of permanence leads to suffering.

- Dukkha (Suffering): Life, according to Buddhism, is inherently unsatisfactory and fraught with suffering. This suffering is not limited to physical or emotional pain, but includes subtle forms of dissatisfaction and the inherent unsatisfactoriness of fleeting pleasures.

- Karma and Rebirth: Karma refers to the moral law of cause and effect, stating that intentional actions have consequences that can affect one’s current life or future lives. Coupled with the belief in rebirth, which is the continuous cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, Theravada Buddhists strive to accumulate good karma and minimize bad karma to improve their circumstances in this life and the next.

- Nibbana: The ultimate goal of Theravada Buddhism is Nibbana, a state of liberation and ultimate peace that lies beyond suffering and the cycles of rebirth. This is achieved through diligent practice and following the Noble Eightfold Path.

These teachings form the foundation of Theravada Buddhism, guiding its followers towards ethical living, self-understanding, and ultimately, the attainment of Nibbana.

Key Practices of Theravada Buddhism

The practices of Theravada Buddhism encompass a wide range of spiritual and ethical disciplines, designed to foster mindfulness, ethical conduct, and wisdom. These practices are primarily aimed at achieving Nibbana, the cessation of suffering and cycle of rebirth.

Adherence to the Five Precepts: Lay followers of Theravada Buddhism are expected to adhere to the Five Precepts, fundamental ethical guidelines for daily life. These include abstaining from taking life, taking what is not given (stealing), sexual misconduct, false speech, and intoxicants that cloud the mind.

Generosity (Dana): Dana, or generosity, is a fundamental practice in Theravada Buddhism. Lay followers often give alms and support to the monastic community, a practice that serves to reduce selfishness and attachment to material goods.

Meditation: Meditation is central to Theravada Buddhism and is used as a tool for cultivating mindfulness and wisdom. Two principal forms of meditation are practiced: Samatha meditation, which develops mental focus, and Vipassana meditation, which cultivates awareness and understanding of the impermanence of all phenomena, the inherent unsatisfactoriness of existence, and the concept of non-self.

Observance of Uposatha Days: Uposatha days are observed on the full moon, new moon, and the two quarter moon days of each lunar month. On these days, lay followers often visit local temples to make merit, listen to Dhamma talks, meditate, and observe the Eight Precepts, which include the Five Precepts plus additional rules such as refraining from eating after midday and abstaining from entertainment and adornments.

Study of the Dhamma: The Dhamma, the teachings of the Buddha as preserved in the Pali Canon, is regularly studied and discussed in Theravada communities. This study aids in developing right understanding, one of the aspects of the Noble Eightfold Path.

Monastic Retreats (Vassa): Monks undertake a three-month retreat during the rainy season (Vassa), staying in one place, often a monastery or temple. During this time, they engage in intensive meditation and Dhamma study. Lay followers often take this period as an opportunity to make merit, donate to the monastic community, and intensify their own practice.

Pilgrimage (Yatra): While not mandatory, many Theravada Buddhists undertake pilgrimages to important historical sites associated with the life of the Buddha, such as Lumbini (his birthplace), Bodh Gaya (where he attained Enlightenment), Sarnath (where he gave his first sermon), and Kushinagar (where he passed away or attained Parinirvana).

The Difference between Mahayana and Theravada Buddhism

Mahayana and Theravada are two significant schools of Buddhism, each with distinct interpretations and emphases in their teachings and practices. While they share a common foundation in the teachings of Gautama Buddha, their philosophical and cultural differences have developed over centuries.

1. Philosophical differences:

- Theravada Buddhism adheres strictly to the teachings found in the Pali Canon, the earliest recorded Buddhist scriptures, and seeks to preserve the original teachings of the Buddha. It emphasizes personal liberation (Nibbana) through individual effort, achieved primarily through the practice of meditation and mindfulness, adherence to ethical precepts, and the understanding of the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path.

- Mahayana Buddhism, which means “Greater Vehicle,” adopts a more liberal and comprehensive approach. It places a significant emphasis on the Bodhisattva ideal. A Bodhisattva is a person who seeks enlightenment not only for their own liberation but also vows to help all sentient beings achieve liberation. Thus, Mahayana Buddhism encourages collective salvation, contrasting with the individual liberation focus of Theravada.

2. Scriptural differences:

- Theravada Buddhism bases its teachings primarily on the Pali Canon or the Tipitaka, believed to be the earliest recorded Buddhist scriptures.

- Mahayana Buddhism, while recognizing the Pali Canon, also includes a vast body of additional texts known as Mahayana Sutras, such as the Lotus Sutra and the Heart Sutra. These texts introduce many new teachings and deities not found in the Pali Canon.

3. Practices and rituals:

- Theravada Buddhism puts a strong emphasis on monasticism. Monks and nuns are considered to be living the ideal lifestyle for achieving Nibbana. Lay followers support the monastic community and follow ethical precepts, but the path to Nibbana is seen as a more monastic pursuit.

- Mahayana Buddhism presents a more accessible path to enlightenment for laypeople, emphasizing that everyone, not just monks and nuns, can aspire to become a Bodhisattva and achieve Buddhahood. It also includes a broader range of practices, such as chanting and devotion to Bodhisattvas and various celestial Buddhas.

4. Geographical spread:

- Theravada Buddhism is predominant in Southeast Asian countries, including Sri Lanka, Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia.

- Mahayana Buddhism is more prevalent in East Asia, including China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and Tibet (where it has developed into Vajrayana Buddhism, often considered a branch of Mahayana).

These differences should be viewed in the context of a shared commitment to the fundamental principles taught by Gautama Buddha, including morality, mindfulness, and wisdom. Both schools have a common goal: the alleviation and ultimate cessation of suffering. Despite their differences, both schools of Buddhism offer pathways toward this goal, shaped by cultural, historical and philosophical influences.

The Development of Theravada Buddhism in Europe and America

The introduction of Theravada Buddhism to the West can be traced back to colonial encounters with Southeast Asian countries, academic interest in Buddhist philosophy, and the arrival of Asian immigrant communities. However, the establishment of Theravada practice in Europe and America took shape more concretely through two main conduits: the dissemination of meditation practices and the establishment of monastic communities.

1. The Dissemination of meditation practices:

In the latter half of the 20th century, there was a growing interest in mindfulness and meditation practices in the West. The Insight Meditation movement, known as Vipassana, emerged as a popular form of Buddhist practice in North America.

Pioneers such as Jack Kornfield, Sharon Salzberg, and Joseph Goldstein trained in Theravada countries and returned to the United States to teach meditation. They established centers like the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts, that have since become focal points for the practice and teaching of Theravada meditation in the West.

2. The establishment of monastic communities:

The founding of Theravada monastic communities in the West played a crucial role in the development of Theravada Buddhism in these regions. This began with the arrival of immigrant communities, particularly from Thailand, Sri Lanka, and Cambodia, who established temples and monasteries in their new homes to continue their traditional religious practices. These centers often served dual roles as places of worship for immigrant communities and as teaching centers for interested Westerners.

One significant figure in the establishment of Western monastic Theravada was the British monk Ajahn Chah, who, together with his Western students, set up a network of monasteries in the tradition of the Thai Forest Sangha. Branch monasteries, like Amaravati and Chithurst in the UK, Abhayagiri in the US, and Bodhinyana in Australia, have since become prominent centers for the teaching and practice of Theravada Buddhism in the West.

The growth of Theravada Buddhism in Europe and America has resulted in an increasing number of Westerners ordaining as monks and nuns and a growing population of lay practitioners. While Theravada Buddhism in the West maintains its core teachings, it has also adapted to Western contexts, with a stronger emphasis on meditation practice for laypeople, active roles for women, and engagement with social and ethical issues. It’s a dynamic and ongoing process, reflecting the adaptability and resilience of the Buddhist tradition in new cultural contexts.