Tai Chi, a profound system of mindful movement originating from China, seamlessly combines physical exercise, meditation, and martial arts into a holistic practice. This discipline is rooted in Taoist philosophy and principles of traditional Chinese medicine, embodying the harmonious interplay between Yin and Yang—the complementary forces of nature.

What is Tai Chi?

Tai Chi also known as Tai Chi Chuan, is a traditional Chinese martial art renowned for its health benefits and meditative properties. Originating from the philosophical principles of Taoism, Tai Chi is characterized by a unique blend of combat technique, physical exercise, and mental discipline, promoting an integrated approach to physical health, mental well-being, and spiritual growth.

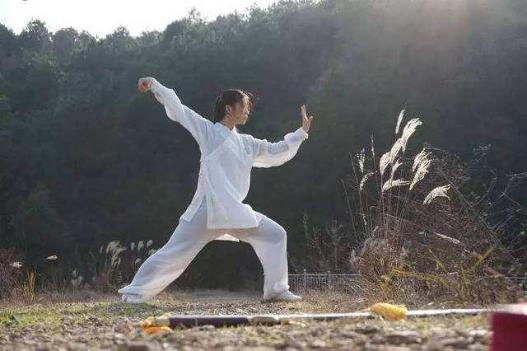

The martial art form, usually practiced for its health benefits, is expressed through slow, gentle, and flowing movements. Tai Chi is often described as “meditation in motion” or “moving meditation,” as the practice facilitates a mindful focus on the body’s movements, enhancing bodily awareness and promoting mental tranquility. Tai Chi emphasizes deep, diaphragmatic breathing and the harmonious interplay of ‘yin’ and ‘yang’ forces within the body, integrating the principles of balance, stability and fluidity.

The name Tai Chi Chuan translates as “supreme ultimate fist” or “boundless fist.” ‘Tai Chi’ signifies the philosophical state of undifferentiated absolute and infinite potential, a dynamic state of oneness before duality emerges. ‘Chuan,’ which means ‘fist,’ denotes the martial aspect of Tai Chi.

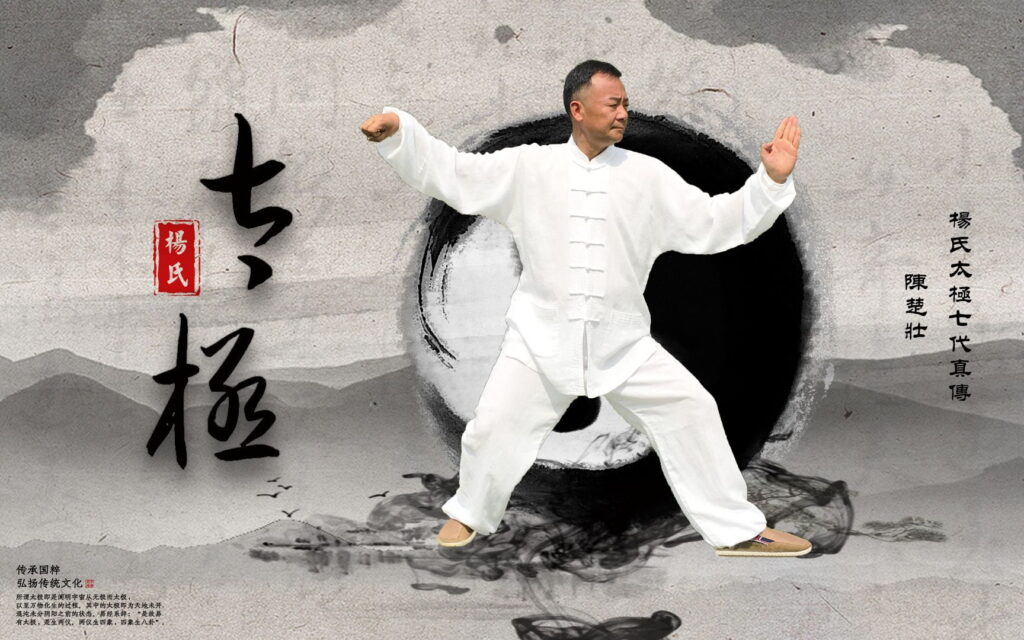

The art of Tai Chi is organized into various styles, the most common of which include Yang, Chen, Wu, and Sun. Each style is defined by distinct technical characteristics, such as pace, the magnitude of movement, and emphasis on specific Tai Chi principles.

Recent scientific studies have corroborated the beneficial effects of Tai Chi on health. Regular practice has been shown to improve balance and flexibility, reduce the risk of falls, particularly in older adults, and alleviate symptoms of stress and anxiety. Tai Chi also contributes to cardiovascular health, with evidence suggesting a reduction in blood pressure among regular practitioners. Additional research has indicated that Tai Chi may also provide benefits for individuals with neurological conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease, and musculoskeletal conditions, such as arthritis.

History of Tai Chi

The history of Tai Chi (or Taijiquan) is deeply interwoven with Chinese history and philosophy, encapsulating the profound influence of Taoism and Buddhist principles on Chinese culture.

The origins of Tai Chi are shrouded in legend and myth, with many attributing its genesis to Zhang Sanfeng, a semi-mythical Taoist monk. According to folklore, Zhang created Tai Chi after witnessing a fight between a snake and a crane, deriving inspiration from their fluid movements and defensive techniques. However, concrete historical evidence regarding Zhang’s involvement in the creation of Tai Chi is lacking, and many scholars argue this account may be more myth than fact.

The earliest verifiable history of Tai Chi can be traced back to the mid-17th century, during the late Ming to early Qing dynasty period. The martial art form was developed by the Chen family in the Henan province’s Chenjiagou village. Chen Wangting, a retired military officer, is widely recognized as the progenitor of Tai Chi. He is believed to have integrated his martial art expertise with Taoist meditative breathing and principles of Chinese medicine to formulate the first Tai Chi Chuan routines.

Tai Chi was kept a closely guarded secret within the Chen family for generations. The art form gained broader exposure when Yang Luchan (1799–1872), later known as the founder of the Yang style, was allowed to learn it. Yang, breaking with the tradition of exclusivity, began teaching Tai Chi to the public, leading to its widespread dissemination across China.

Throughout the years, various Tai Chi styles have been developed, the most recognized being Chen, Yang, Wu (Hao), Wu, and Sun. Each style, while retaining the fundamental principles of Tai Chi, features different characteristics. For example, the Chen style is known for its silk reeling technique, which involves alternating fast/slow motion and bursts of power, while the Yang style is characterized by its gentler, flowing movements and larger frame.

During the 20th century, Tai Chi gained international popularity, spreading to the West as a result of increased global cultural exchange. The art form was frequently marketed for its health benefits, with “simplified” forms designed to make it more accessible to the general public. Consequently, Tai Chi has evolved from a martial art to a holistic exercise regimen that combines physical movement, meditation and breathing techniques.

The different styles of Tai Chi

Tai Chi, while underpinned by universal principles and techniques, is expressed through diverse styles. Each style, despite being rooted in common theory and methodology, carries a unique signature that reflects the insights and emphasis of its founder. The five primary styles of Tai Chi are named after the Chinese families who developed them: Chen, Yang, Wu (Hao), Wu, and Sun.

- Chen style: The oldest of all the styles, the Chen style was created in the 17th century by Chen Wangting, a retired military officer from the Henan province. Chen style is distinctive for its silk reeling (Chansijin) technique, which is a spiraling movement that flows through the body. Chen practitioners alternate between slow, graceful movements and short, quick bursts of power, often with leaps and stomps. The style is known for its low stances and complex, demanding forms, which makes it physically more challenging than some of the other styles.

- Yang style: Developed by Yang Luchan (1799-1872), the Yang style is the most popular and widely practiced around the world. Yang, initially a student of the Chen family, modified the form to be gentler and more suitable for all age groups and fitness levels. Yang style is characterized by slow, steady, and even movements, large and expansive postures, and a clear emphasis on the internal aspects of Tai Chi, including breath control and cultivation of Qi, the vital energy within the body.

- Wu (Hao) style: Wu Yuxiang (1812-1880) established the Wu (Hao) style after studying under both Yang Luchan and a member of the Chen family. The Wu (Hao) style focuses on compact, small frame movements and emphasizes the internal development of energy. It incorporates a higher stance than the Chen style and emphasizes balance, subtlety, and internal power.

- Wu style: This style was created by Wu Quanyou, a military officer who was one of Yang Luchan’s top students. His son, Wu Jianquan, further developed the style. The Wu style is characterized by medium-sized, compact movements, making it suitable for practitioners with limited space. Its movements are generally performed slowly, with a focus on relaxation and softness.

- Sun style: The youngest of the primary styles, the Sun style was created by Sun Lutang (1861-1932), a renowned master who also had expertise in Xingyiquan and Baguazhang, two other Chinese martial arts. Sun style combines the best elements of these martial art forms with Tai Chi, resulting in a distinctive approach. It is known for its agile steps, higher stances, and a strong emphasis on Qigong (energy cultivation) for its health benefits.

Each of these styles, despite their differences, remains true to the core principles of Tai Chi: the balance of Yin and Yang, the interplay of softness and strength, and the integration of body, mind and spirit. They all serve to promote health, mindfulness, and martial artistry, offering different pathways to explore and experience the rich tapestry of Tai Chi.

The principles of Tai Chi practice

Tai Chi is underpinned by a set of essential principles. These principles, deeply rooted in Taoist philosophy and traditional Chinese medicine, guide Tai Chi practitioners in their journey towards physical fitness, mental equilibrium and spiritual growth.

- Integration of Mind and Body: A fundamental tenet of Tai Chi is the harmonious unification of the mind and body. The mind, through focused attention, guides the body’s movements, and the body, in turn, influences the state of the mind. This principle of mutual interplay leads to a heightened awareness of the self, promoting balance, coordination and tranquility.

- Continuity and Flow: Tai Chi movements are characterized by their continuous, flowing nature, mirroring the Taoist concept of the universe as an unbroken flow of energy (Qi). Each movement in Tai Chi is connected to the next, ensuring an uninterrupted, smooth transition from one posture to another. This principle cultivates flexibility and fluidity, both physically and mentally.

- Softness overcomes hardness: This principle, a central theme in Taoist philosophy, posits that gentleness and flexibility triumph over brute force. In Tai Chi, this is expressed through yielding and redirecting force rather than resisting or opposing it directly. It underscores the art’s defensive martial arts techniques and fosters resilience and adaptability.

- Balance and Harmony: The concept of Yin and Yang, representing complementary opposites, is integral to Tai Chi. Movements in Tai Chi aim to balance these opposing yet interconnected forces. The principle extends beyond the physical realm to include balancing effort and relaxation, exertion and recovery, and internal and external focus.

- Rooting and Centering: Rooting refers to the concept of maintaining a stable connection with the ground, promoting balance and power. Centering, often referred to as “sinking the Qi,” encourages practitioners to focus their energy towards the lower abdomen or “dantian”, fostering stability and calmness.

- Breath control: Tai Chi involves deep, diaphragmatic breathing coordinated with movements. Breathing is viewed as the bridge between the mind and body, aiding in relaxation, concentration, and the internal flow of Qi.

- Natural, relaxed movement: Movements in Tai Chi are performed naturally, without strain or tension. This principle promotes ease of movement, preventing undue stress on the joints and muscles.

You have to understand and integrate these principles to reaping the full benefits of Tai Chi. They serve not just as a guide for practice, but also as a philosophical framework for cultivating a harmonious, balanced lifestyle.

Tai Chi equipment

Tai Chi requires minimal equipment. This aspect of Tai Chi makes it accessible and straightforward to practice in various settings. Nonetheless, there are certain items that can enhance the practice and ensure the comfort and safety of the practitioner.

- Clothing: The most important aspect of Tai Chi equipment is clothing. Practitioners should wear loose, comfortable clothes that do not restrict movement. Traditional Tai Chi uniforms, often made of silk or cotton, are available but not required. These uniforms typically consist of a loose-fitting shirt and pants, allowing for unrestricted movement of all joints.

- Footwear: Proper footwear is also vital in Tai Chi practice. Shoes should be flat-soled to help maintain balance and stability, and they should be comfortable and flexible to allow free movement of the feet and toes. Traditional Tai Chi shoes are available, often made of canvas or leather, with a thin, flat sole. However, any comfortable flat-soled shoe, or even bare feet, can be suitable, depending on the practice surface and personal preference.

- Tai Chi swords: While Tai Chi is often practiced as a form of exercise and meditation, it is fundamentally a martial art. Some advanced forms incorporate traditional weapons, such as the straight double-edged sword (Jian) and the single-edged sword (Dao). These forms are typically practiced with specially designed Tai Chi swords, which are lightweight and flexible.

- Tai Chi fans: In some styles, a Tai Chi fan is used as a prop in forms, introducing dynamic, flowing movements that mimic traditional martial arts techniques. Tai Chi fans are typically made of bamboo and fabric, and they open and close smoothly for quick, sweeping movements.

- Mats: While not a requirement, some practitioners may choose to use a yoga or exercise mat for comfort, especially when practicing in outdoor or hard-surfaced areas.

- Instructional materials: Books, DVDs, online tutorials, and other instructional materials can supplement in-person training, especially for beginners or those practicing at home.

Tai Chi does not necessitate significant equipment. However, appropriate attire and footwear, and in certain advanced forms, swords or fans, can enhance practice. Furthermore, instructional materials can supplement learning and practice. Even so, LotusBuddhas would like to emphasize that remains on the practitioner’s own body and mind, as the integration of physical movement, meditation, and breath control is central to Tai Chi.

How to practice Tai Chi for beginners

Tai Chi offers numerous benefits for practitioners of all skill levels. For beginners, approaching Tai Chi might seem daunting due to its apparent complexity. Don’t worry! LotusBuddhas has prepared the following steps to provide you with a structured approach to begin this profound practice.

- Understanding the philosophy: Beginners should first acquaint themselves with the underlying philosophy of Tai Chi. It is essential to understand that Tai Chi is not just a physical exercise, but a holistic practice promoting the integration of mind and body, inspired by the principles of Taoism and traditional Chinese medicine.

- Finding a qualified instructor: While numerous resources and self-learning materials are available, it is highly recommended that beginners find a qualified Tai Chi instructor. A good instructor provides precise guidance, instant feedback, and can tailor a routine to suit individual needs, thereby ensuring safety and effectiveness.

- Choosing a style: As a beginner, understanding the various styles of Tai Chi and choosing the most suitable one can enhance the learning experience. While the Yang style, with its gentle and flowing movements, is often recommended for beginners, the choice should be based on personal preference and comfort.

- Beginning with basic movements: Start with learning and mastering basic Tai Chi movements. A typical Tai Chi class begins with a warm-up involving gentle stretches and movements to relax the body and mind. Following this, one may learn a series of movements called forms. For beginners, instructors often teach short, simplified forms which are less complex but incorporate essential Tai Chi principles.

- Focusing on breath and movement coordination: Tai Chi emphasizes the coordination of breath and movement. As a beginner, one should learn to synchronize slow, deep breaths with each movement, enhancing concentration and promoting relaxation.

- Practicing regularly: Like any skill, regular and consistent practice is crucial in Tai Chi. Beginners should aim for shorter, more frequent sessions—about 15 to 20 minutes a day—to develop consistency and progressively improve their form and technique.

- Maintaining patience and perseverance: Tai Chi is a journey of personal growth and self-discovery, not a destination. Beginners should approach their practice with patience and an open mind. Progress may be slow, and challenges are expected, but maintaining a positive and patient attitude can foster a rewarding and beneficial Tai Chi practice.

This is just a basic guide for you to grasp the foundation of Tai Chi. Honestly, Tai Chi encompasses much more than simply learning physical movements. It requires a deep understanding of its underlying philosophy, choosing a suitable style, learning from a skilled instructor, and cultivating patience and perseverance. With time and practice, Tai Chi can become a valuable tool to enhance physical health, achieve mental equilibrium and overall well-being.

The health benefits of Tai Chi

Tai Chi has gained significant attention for its health-promoting benefits. The practice combines physical movement, mindfulness, and breath control, making it an integrative, holistic exercise method. Evidence from clinical research and observational studies supports a range of physical and mental health benefits associated with regular Tai Chi practice.

- Physical fitness: Tai Chi is a low-impact, moderate-intensity exercise suitable for individuals of all ages and fitness levels. It can help improve physical fitness by increasing strength, flexibility, balance, and aerobic capacity. The movements in Tai Chi engage various muscle groups, promoting muscle tone and strength. Its emphasis on balance and coordination can help reduce the risk of falls, especially among older adults.

- Cardiovascular health: Regular Tai Chi practice has been associated with improved cardiovascular health. Studies suggest it may help lower blood pressure, reduce cholesterol levels, and improve overall heart health. Tai Chi’s moderate aerobic activity and stress-reducing qualities are likely contributors to these benefits.

- Bone health: Preliminary research suggests that Tai Chi may contribute to bone health. Its weight-bearing and resistance movements may help slow bone loss in postmenopausal women, thereby reducing the risk of osteoporosis.

- Chronic conditions: Tai Chi may help manage several chronic conditions such as arthritis, fibromyalgia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Its gentle, flowing movements can help alleviate pain and stiffness, enhance physical function, and improve quality of life in individuals with these conditions.

- Mental health: Tai Chi is a mind-body exercise promoting mindfulness and relaxation, which can contribute to improved mental health. Regular practice has been associated with reduced stress, anxiety, and depression, and improved mood and overall mental well-being. Furthermore, its emphasis on concentration and coordination can enhance cognitive function, potentially slowing cognitive decline in older adults.

- Sleep quality: Research suggests that practicing Tai Chi can improve sleep quality. Its relaxation and stress-reducing effects likely contribute to better sleep, thereby supporting overall health and well-being.

- Immune function: Preliminary research suggests that Tai Chi may enhance immune function and inflammatory response, potentially reducing susceptibility to illnesses and promoting faster recovery.

As always, despite the significant health benefits Tai Chi brings, LotusBuddhas advises you that it is a supplementary method for health. Individuals with existing health conditions should consult healthcare experts before starting Tai Chi practice and should not replace conventional medical treatment unless recommended by healthcare providers.

– You can learn more about the scientific research on the health benefits of Tai Chi: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28661865/

Some misconceptions about Tai Chi

While Tai Chi has been recognized globally for its health and wellness benefits, several misconceptions persist due to cultural differences, lack of information, and misinterpretations. The following are some commonly encountered misconceptions about Tai Chi:

- Tai Chi is only for the elderly: Although Tai Chi is often recommended for older adults due to its low-impact and gentle movements, it is not exclusive to this demographic. Tai Chi can be beneficial for people of all ages, and its practice can be adjusted according to the individual’s fitness level and health condition.

- Tai Chi is merely a form of exercise: While Tai Chi is indeed a form of physical exercise, reducing it to just that oversimplifies its nature. Tai Chi is a holistic mind-body practice, integrating physical movements with mindfulness and breath control. It also serves as a martial art, a meditative process, and a means of cultivating life energy.

- Tai Chi does not provide a cardiovascular workout: Though Tai Chi is a low-impact and typically slow-paced activity, it does involve moderate aerobic activity, especially in advanced and vigorous forms. As such, regular Tai Chi practice can contribute to cardiovascular health.

- Tai Chi is easy to learn: Tai Chi’s graceful and flowing movements might give the impression that it is easy to learn. However, the art requires considerable practice and patience to master the intricacies of the forms and to fully integrate the mind-body principles it embodies. The subtleties of movement, balance, coordination, and breath control can be challenging to perfect.

- Tai Chi is a religious practice: While Tai Chi is rooted in Taoist philosophy and incorporates principles of traditional Chinese medicine, it is not a religious practice. People of all religious backgrounds or none can practice Tai Chi. The philosophical aspects are more geared towards understanding human nature and the natural world rather than adherence to a particular religious belief system.

- All Tai Chi styles are the same: There are several styles of Tai Chi, including Yang, Chen, Wu, and Sun, each with distinct characteristics, forms, and techniques. Some styles may be more slow-paced and gentle, while others can be more dynamic and martial in nature.

In summary, while misconceptions about Tai Chi still exist, clear understanding and education can dispel these inaccuracies. If you have the opportunity to visit Vietnam, you will easily encounter many people practicing Tai Chi movements in the parks during the morning. With its multifaceted nature and numerous benefits, Tai Chi is regarded as a valuable form of exercise for physical health, mental well-being, and overall personal development.