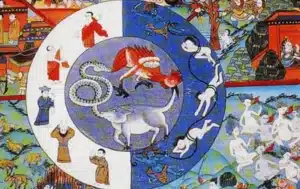

Within the vast landscape of Buddhist philosophy lies a profound concept known as the Ten Worlds. This intricate framework paints a vivid picture of the full spectrum of human experience, encompassing both suffering and enlightenment. Each of these ten realms represents a distinct state of being, characterized by specific mental states, emotions, and karmic consequences.

- Hell (Jigoku): This realm symbolizes the intense suffering arising from negativity and clinging to delusion. It manifests as a state of burning pain, torment, and isolation, reflecting the internal hell of unwholesome karma.

- Hungry Ghosts (Gaki): Insatiable craving and unfulfilled desires are the hallmarks of the Gaki realm. Individuals here are consumed by hunger and thirst, yet they are unable to find true satisfaction, leading to constant frustration and despair.

- Animality (Chikusho): This realm embodies the instinctive and primal nature of existence, characterized by limited awareness and driven by survival needs. Beings here lack access to higher teachings and understanding, leading to a cycle of struggle and suffering.

- Anger (Shura): The fires of anger and hatred burn brightly in the Shura realm. Individuals here are consumed by envy, competition, and violence, creating a turbulent atmosphere of conflict and distrust.

- Humanity (Nin): This realm represents the state of ordinary human existence, characterized by a mixture of joy and suffering, good and evil. Individuals here have the capacity for both compassion and cruelty, making the path towards enlightenment a constant challenge.

- Heaven (Ten): This realm reflects a state of contentment and pleasure, free from suffering and filled with beauty and abundance. However, even in this realm, individuals remain susceptible to attachment and delusion.

- Voice-Hearers (Engaku): In this realm, individuals develop the ability to hear and understand the teachings of the Buddha, leading to a deeper understanding of the Dharma and the path towards liberation.

- Bodhisattvas (Bosatsu): This realm signifies a profound commitment to the path of enlightenment, not only for oneself but for all beings. Bodhisattvas dedicate their lives to helping others and practicing compassion, accumulating vast merit along the way.

- Buddhahood (Butsu): This ultimate state of being represents the complete liberation from suffering and the attainment of perfect enlightenment. Buddhas possess boundless wisdom, compassion, and understanding, guiding others on the path towards liberation.

- Mystic Law (Myoho): This realm symbolizes the core principle of Nichiren Buddhism, emphasizing the inherent Buddhahood within all beings and the transformative power of chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo.

Understanding the Ten Worlds offers valuable insights into the complexities of human existence and the interconnectedness of all living beings. It serves as a guide for navigating the challenges and opportunities we encounter throughout our lives, encouraging us to cultivate compassion, wisdom, and a commitment to the path of enlightenment.

By exploring these diverse realms, we gain a deeper understanding of ourselves and our place within the universe. We learn to recognize the consequences of negativity and the transformative potential of positive actions. Ultimately, the Ten Worlds empower us to embrace the full spectrum of human experience, cultivate a sense of responsibility for our own lives, and work towards creating a more harmonious and enlightened world for all.

1. Hell (jigoku)

Within the vast landscape of Buddhist philosophy lies the concept of the Ten Worlds, a spectrum of states of being encompassing both suffering and enlightenment. Amongst these, Jigoku, the Buddhist Hell, stands as a stark reminder of the consequences of negativity and clinging to delusion.

Jigoku is not a place of eternal damnation, as depicted in some Western traditions. Instead, it is viewed as a temporary state of suffering arising from unwholesome karma, namely, actions motivated by greed, hatred, and delusion. These mental poisons create an internal hell, characterized by intense pain and torment, both physical and mental.

The specific experiences of Jigoku vary depending on the severity of one’s karma and the particular Buddhist school. However, common themes include:

- Extreme heat and cold: The fires of Jigoku are not literal flames, but rather represent the burning sensations of anger and hatred consuming the being. Conversely, the icy cold symbolizes the numbness of ignorance and lack of compassion.

- Hunger and thirst: These represent the insatiable desires that plague those trapped in delusion. No matter how much they acquire, their cravings remain unfulfilled, leading to constant suffering.

- Demons and torturers: These symbolize the internal demons of fear, doubt, and negativity that torment the mind and prevent spiritual progress.

- Isolation and loneliness: The intense suffering in Jigoku leads to a sense of isolation and disconnection from others. This further amplifies the experience of pain and reinforces a sense of hopelessness.

However, even within the depths of Jigoku, the potential for liberation exists. The flames of suffering can become the catalyst for awakening, prompting the individual to recognize the error of their ways and seek refuge in the Dharma. Through acts of compassion, generosity, and meditation, one can begin to break free from the chains of negativity and climb towards higher realms of existence.

The concept of Jigoku serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of mindful action and cultivating positive mental states. While it may appear daunting, it ultimately offers a transformative message of hope and liberation. By understanding the consequences of negativity and striving towards a life of virtue, we can avoid the fires of Jigoku and pave the way for a brighter future, not only for ourselves but for all beings.

2. Hunger Ghosts (gaki)

Hungry ghost, these tormented beings epitomize the state of insatiable craving, forever hungry and thirsty but unable to find fulfillment. Trapped in this realm of constant suffering, the Gaki experience a distorted reflection of our own desires. Their bodies are thin and emaciated, with distended bellies and long, thin necks symbolizing their inability to nourish themselves. Despite consuming vast amounts of food and drink, they can never satiate their hunger and thirst.

This insatiable craving stems from the karma of greed, jealousy, and possessiveness. During their lifetimes, the Gaki may have accumulated wealth or resources without sharing or practicing generosity. Now, in this realm, their greed manifests as a constant yearning that can never be quenched.

The suffering of the Gaki extends beyond physical hunger and thirst. They are also plagued by mental torment, experiencing feelings of envy, frustration, and despair. Unable to escape their own torment, they often wander aimlessly, seeking anything that might offer relief, even if it is temporary and ultimately unsatisfying.

However, even within this realm of suffering, there exists a glimmer of hope. The Gaki are not condemned to eternal torment. Their suffering can serve as a wake-up call, urging them to recognize the error of their ways and seek liberation. Through acts of generosity, compassion, and offering merit, they can begin to break free from the cycle of craving and ascend to higher realms of existence.

The gaki, therefore, serve as a powerful reminder of the consequences of clinging to greed and unwholesome desires. Their presence urges us to practice mindful consumption, cultivate generosity, and let go of attachment. By understanding their plight, we can gain a deeper understanding of our own desires and strive to cultivate a more balanced and fulfilling life, avoiding the pitfalls of insatiable craving and finding true contentment within ourselves.

3. Animality (Chikusho)

Chikusho embodies the characteristics of the animal kingdom – driven by instinct, survival, and the pursuit of basic needs. Beings in this realm lack the intellectual and spiritual faculties to comprehend higher teachings or engage in complex moral reasoning. Their lives are governed by primal instincts such as hunger, fear, and desire, leading to a constant struggle for existence.

The specific conditions of Chikusho vary depending on the individual’s karma. However, some common themes include:

- Predation and prey: The constant threat of being preyed upon or becoming prey themselves creates an atmosphere of fear and insecurity. This reinforces the ‘eat or be eaten’ mentality, highlighting the harsh realities of survival in the animal realm.

- Limited awareness: Driven by primal instincts and lacking higher cognitive abilities, beings in Chikusho have a limited understanding of the world and their place within it. This can lead to frustration and confusion, further perpetuating the cycle of suffering.

- Ignorance of the Dharma: Without access to spiritual teachings or the ability to grasp them, beings in Chikusho remain unaware of the path towards liberation. This can create a sense of hopelessness and despair, hindering their progress towards higher states of existence.

Despite the challenges and suffering inherent in Chikusho, it is not solely a realm of despair. It can serve as a stepping stone on the path towards enlightenment. By observing the limitations and suffering within this realm, individuals can develop compassion for all beings and understand the dangers of clinging to desires and instincts.

Furthermore, karmic acts of generosity and kindness can aid in elevating one’s state of being. By helping other beings in need, offering food and shelter to animals, and practicing non-violence, individuals can accumulate merit and gradually ascend to higher realms, ultimately seeking liberation from all forms of suffering.

The world of Chikusho, therefore, offers a valuable lesson in understanding the interconnectedness of all beings. It reminds us of the impermanence of existence, the dangers of clinging to desires, and the importance of cultivating compassion for all living creatures. By learning from the struggles within this realm, we can navigate the instinctive aspects of our own nature with greater awareness and understanding, ultimately creating a more harmonious and compassionate world for all.

4. Anger (shura)

This turbulent realm, often depicted as a battlefield, embodies the destructive power of anger, hatred, and jealousy. Individuals in Shura are consumed by a fiery rage, constantly engaged in battles, both internal and external. Their minds, clouded by anger and resentment, distort reality, leading to a constant cycle of conflict and suffering. This relentless hostility creates an atmosphere of hostility and distrust, making it nearly impossible to experience peace or joy.

The specific manifestations of Shura vary depending on the individual’s karma. However, some common themes include:

- Competitiveness and envy: Constant comparisons with others fuel the flames of jealousy and anger. The desire to be superior, to win at all costs, leads to endless conflict and dissatisfaction.

- Violence and aggression: Anger manifests as physical and verbal aggression, both towards others and oneself. This destructive behavior creates a ripple effect of suffering, perpetuating the cycle of violence.

- Distorted perception: Fueled by anger, the mind loses its ability to perceive reality clearly. Suspicion and mistrust cloud judgment, leading to misinterpretations and further conflict.

Trapped in the fires of Shura, individuals experience profound suffering. Their relationships are strained by anger and distrust, and their minds are consumed by negativity. It is a realm of constant agitation and turmoil, offering little opportunity for peace or self-reflection.

However, despite the bleakness of Shura, hope remains. The intense suffering experienced here can serve as a wake-up call, prompting the individual to recognize the destructive nature of anger and seek liberation.

Through practicing mindfulness, cultivating compassion, and engaging in acts of generosity, individuals can begin to cool the flames of anger and step onto the path towards inner peace. By understanding the root causes of their anger and learning to let go of resentment, they can gradually ascend to higher realms of existence.

The world of Shura, therefore, serves as a potent reminder of the dangers of clinging to anger and hatred. It highlights the importance of developing emotional self-regulation, practicing forgiveness, and cultivating a forgiving and compassionate heart. By learning to navigate the flames of Shura with mindfulness and understanding, we can create a more peaceful and harmonious world for ourselves and others.

5. Humanity (Nin)

The state of “Humanity” or “Tranquility,” known as “Nin” in the Buddhist schema of the Ten Worlds, represents a relatively calm and rational state of being. Unlike the lower four worlds, which are primarily driven by instinctual and reactive behaviors, Humanity is a state where individuals can think and act more deliberately.

In the world of Humanity, individuals have the capacity to exercise reason, make free decisions, and exert some control over their emotions and instincts. There is an element of self-awareness and a capacity to reflect on one’s actions and their consequences. This allows for the cultivation of ethical conduct and the ability to take considered action, rather than being impulsively driven by desires or fears.

This state, however, does not equate to a permanent condition of tranquility or unshakeable peace. Individuals in the state of Humanity can still experience a wide range of emotions, including joy, sadness, anger, and fear. They can also be influenced by external circumstances, and their tranquility can be disturbed when faced with difficulties or challenges.

Moreover, while the world of Humanity allows for the exercise of reason and ethical conduct, it does not necessarily imply the presence of wisdom or a deep understanding of life’s ultimate truths. It represents a kind of ‘ordinary’ human condition, where one is not dominated by base desires or destructive impulses, but has yet to attain the profound insight or compassion of the higher states.

Yet, as with all other states within the Ten Worlds, the state of Humanity inherently contains the potential for Buddhahood. It is within this ordinary human condition, with all its imperfections and vulnerabilities, that the capacity for enlightenment exists. The challenge lies in recognizing and activating this latent potential, thereby transforming the state of Humanity into a higher state of life.

6. Heaven or Rapture (Ten)

In the Buddhist schema of the Ten Worlds, “Heaven” or “Rapture,” also known as “Ten,” signifies a state of temporary joy and satisfaction, often stemming from the fulfillment of some desire or the realization of a particular outcome. It should be noted that this state, like others in the Ten Worlds, does not correspond to a physical location but is rather an internal condition or state of life.

Heaven is characterized by feelings of intense happiness, pleasure, or euphoria. This can arise from various sources, such as the gratification of desires, achievement of goals, enjoyment of sensual pleasures, or experiencing love and appreciation. However, this joy is transient and dependent on external circumstances.

A crucial characteristic of this state is its dependency on external conditions. The happiness experienced in the state of Heaven is typically contingent upon specific factors or conditions being met. This could involve obtaining a desired object, achieving a particular status, or maintaining a certain relationship. As such, the joy experienced in this state is fleeting and vulnerable to changes in circumstances.

Further, while the state of Heaven involves experiencing pleasure or happiness, it does not necessarily entail a deep understanding of the nature of life or reality. It is a state that can be easily disturbed or disrupted by changes in external conditions or by the arising of negative feelings or circumstances.

Yet, in line with the doctrine of the Ten Worlds, the state of Heaven also contains the potential for enlightenment. Despite its transient and dependent nature, this state is not devoid of the capacity for Buddhahood. The challenge lies in recognizing this inherent potential and consciously striving towards it, transforming the temporary joy of Heaven into the enduring, profound joy of Buddhahood.

7. Voice-Hearers (Engaku)

This realm signifies an awakening, a transition from the limitations of the lower worlds towards the expansive wisdom of enlightenment.

Imagine yourself standing at the cusp of a mountain range, the lower slopes shrouded in mist, while the peaks bathed in the golden light of dawn. This is the essence of Engaku: a state of being where the individual begins to perceive the world with new clarity, having received the teachings of the Buddha.

Unlike the lower realms where suffering and delusion reign, Engaku opens the doors to a deeper understanding of the Dharma, the Buddhist path to liberation. Individuals in this realm develop the ability to listen attentively, not just with their ears but with their hearts and minds, to the profound truths spoken by the Buddha.

This awakening manifests in several ways:

- Discernment: The veil of ignorance begins to lift, allowing individuals to distinguish between illusion and reality, between true happiness and fleeting pleasures.

- Right view: The teachings of the Buddha provide a framework for understanding the world and one’s place within it, leading to a more balanced and compassionate outlook.

- Ethical conduct: Understanding the principles of karma and the interconnectedness of all beings motivates individuals to engage in virtuous actions, cultivating compassion and generosity.

However, Engaku is not simply a state of passive listening. It demands active engagement with the Dharma, transforming mere understanding into practice. Individuals in this realm begin to integrate the teachings into their lives, diligently applying them to their thoughts, words, and actions.

This process of integrating the Dharma leads to a gradual awakening of the inherent Buddhahood within each individual. As their understanding deepens, their attachment to the self weakens, creating space for greater compassion and wisdom.

The realm of Engaku serves as a beacon of hope, offering a glimpse into the transformative power of the Buddha’s teachings. It reminds us that the path to enlightenment is open to all, and that even a single step towards understanding can ignite the flame of awakening within ourselves.

By diligently studying the Dharma, practicing mindfulness and meditation, and cultivating a compassionate heart, we too can progress on the path of Engaku, eventually ascending to greater heights of wisdom and enlightenment. Remember, the journey begins with a single step, with a willingness to open our ears and hearts to the transformative teachings of the Buddha.

8. Bodhisattvas (Bosatsu)

These noble beings represent the pinnacle of compassion and selfless dedication, embodying the essence of the Mahayana path towards enlightenment.

Imagine a lotus flower, rooted in the depths of the earth yet reaching towards the sun, untouched by the surrounding mud. This is the essence of a Bodhisattva: a being who has emerged from the mire of suffering, yet remains deeply connected to it, motivated by a profound desire to uplift all beings.

Unlike the arhats, who seek individual liberation, Bodhisattvas dedicate themselves to a far grander mission: the liberation of all sentient beings. They have attained a level of understanding and wisdom that allows them to see through the illusion of selfhood, recognizing the interconnectedness of all existence.

This profound understanding manifests in several ways:

- Boundless Compassion: Their hearts overflow with empathy for all beings, regardless of their actions or beliefs. They see the inherent Buddhahood within each individual, even those who may be shrouded in suffering or delusion.

- Selfless Service: Driven by their compassion, Bodhisattvas dedicate their lives to serving others. They tirelessly work to alleviate suffering, guide those lost in darkness, and offer solace to the afflicted.

- Wisdom and Skillful Means: Possessing deep knowledge of the Dharma, Bodhisattvas employ skillful means to guide others towards enlightenment. They tailor their teachings and actions to meet the unique needs and capacities of each individual.

- Patience and Perseverance: The path of a Bodhisattva is long and arduous, filled with challenges and obstacles. Yet, they remain undaunted, fueled by their unwavering commitment to the liberation of all beings.

The realm of the Bodhisattvas serves as a powerful inspiration to us all. It reminds us that our own Buddhahood is inherent, waiting to be awakened. We too can cultivate the boundless compassion of a Bodhisattva, dedicating ourselves to the welfare of others and working tirelessly towards the creation of a world free from suffering.

By practicing compassion, generosity, and wisdom in our daily lives, we can follow in the footsteps of the Bodhisattvas. We can become agents of positive change, contributing to the collective awakening of humanity and illuminating the path towards a brighter future for all. Remember, even the smallest act of compassion, fueled by a genuine desire to help others, can ripple outwards, creating a wave of positive change that extends far beyond ourselves.

9. Buddhahood (Butsu)

Within the intricate tapestry of the Ten Worlds, a cornerstone of Buddhist philosophy, lies the ultimate state of being: Buddhahood (Butsu). This realm represents the culmination of the spiritual journey, the embodiment of perfect enlightenment and boundless wisdom.

Imagine reaching the summit of a majestic mountain, after a arduous climb. From this vantage point, the world unfolds beneath you, bathed in the golden light of a new dawn. This is the essence of Buddhahood: a state of perfect clarity and understanding, where all suffering has been transcended and all illusions have dissolved.

Individuals who have attained Buddhahood have achieved complete liberation from the cycle of birth and death. They are free from the shackles of ignorance, desire, and hatred, and possess boundless compassion and wisdom.

This enlightened state manifests in several ways:

- Perfect Wisdom: Buddhas have a complete understanding of the Dharma, the true nature of reality, and the interconnectedness of all things. They see through the veil of illusion and perceive the world with perfect clarity.

- Boundless Compassion: Their hearts overflow with an infinite love for all beings, encompassing both those who are suffering and those who are already liberated. Their compassion knows no bounds, extending to all corners of the universe.

- Unlimited Skillful Means: Possessing perfect wisdom and compassion, Buddhas are able to guide others towards enlightenment with unparalleled skill. They tailor their teachings and actions to meet the unique needs and capacities of each individual, ensuring that their message resonates deeply.

- Unwavering Joy and Peace: Having transcended all suffering and delusion, Buddhas live in a state of eternal peace and joy. They radiate a calm and serenity that inspires all who come into contact with them.

The realm of Buddhahood serves as a beacon of hope, illuminating the path towards liberation for all beings. It reminds us that our own Buddhahood is inherent, waiting to be awakened. Through diligent practice, unwavering commitment, and boundless compassion, we can too ascend to the summit of the Ten Worlds and attain the ultimate state of enlightenment.

By cultivating the qualities of a Buddha in our daily lives – wisdom, compassion, skillful means, and joy – we begin to walk the path towards enlightenment. Remember, the journey may be long and arduous, but each step we take brings us closer to the summit, where we too can experience the boundless freedom and peace of Buddhahood.

10. Mystic Law (Myoho)

The Mystic Law realm transcends the limitations of individual states of being, representing the fundamental truth that underlies all existence.

Imagine a single drop of water falling into a vast and still lake, causing ripples that expand outward, seemingly endlessly. This metaphor captures the essence of Myoho: a profound truth with the potential to transform every aspect of our lives and the world around us.

Myoho embodies the following:

- Universal Potential: It signifies the inherent Buddhahood within all beings, regardless of their present state of existence. This inherent potential lies dormant within each of us, waiting to be awakened.

- Interconnectedness: Myoho emphasizes the interconnectedness of all things. It reminds us that our individual lives are inextricably linked to the lives of all other beings, and that our actions have far-reaching consequences.

- Dynamic Change: Myoho represents the constant flow of change and transformation that permeates all of existence. Just as the drop of water ripples outward, our actions have the power to create positive change in the world around us.

- Ultimate Reality: Myoho signifies the true nature of reality, which is beyond our limited perception. It encompasses the full spectrum of human experience, from the lowest depths of suffering to the highest peaks of enlightenment.

Unlike the other Ten Worlds, Myoho is not a realm that can be attained or experienced in isolation. It is the universal principle that underlies all existence, the driving force behind all change and transformation.

The practice of Nichiren Buddhism centers around chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, which is a way of aligning ourselves with the dynamic and transformative power of Myoho. Through this practice, we can tap into the inherent Buddhahood within ourselves and begin to manifest its qualities in our daily lives.

By understanding and embracing Myoho, we gain a deeper appreciation for the interconnectedness of all things and the potential for positive change within ourselves and the world. We are empowered to act with compassion, wisdom, and courage, knowing that our actions have the power to ripple outwards, creating a more harmonious and enlightened world for all.

Remember, Myoho is not a distant concept to be grasped only by advanced practitioners. It is the very essence of life itself, present in every moment and within every being. By opening our hearts and minds to its transformative power, we can begin to experience the boundless potential that lies within each of us and contribute to the creation of a more just and compassionate world.

Reference:

- SGI-USA describes The Ten Worlds: https://www.sgi-usa.org/2022/08/11/the-ten-worlds/

- Buddhist Terminology: Ten Worlds: https://nstmyoshinji.org/terminology/ten-worlds/