In Buddhist rituals and practices, one act stands out for its profound symbolism and transformative potential: the act of prostration. On the surface, it is a simple physical gesture—an act of bending the body in reverence. Yet, within this humble gesture lie depths of spiritual meaning that encapsulate the essence of the Buddhist path.

In this article, LotusBuddhas will provide you with the meaning and benefits of prostration in Buddhism, as well as the correct way to practice it so that you can follow along when you visit temples.

What is Prostration?

Across cultures and religions, prostration, the act of bowing deeply with one’s forehead touching the ground, serves as a powerful form of non-verbal communication. It signifies profound respect, complete submission, and unwavering adoration. This universal gesture transcends language and holds deep historical significance, offering a glimpse into our shared human experience.

Prostration in Religious Traditions:

- Buddhism: Buddhists practice prostration as a form of veneration and gratitude towards the Buddha, Dharma (teachings), and Sangha (community). It symbolizes humility, surrender, and the aspiration to attain enlightenment.

- Christianity: In the early Church, prostration was a common practice during prayer, especially during Lent and Holy Week. While less common today, some denominations still incorporate prostration into their worship services.

- Islam: Muslims perform prostration (sujud) during the five daily prayers. It represents complete submission to Allah and a physical manifestation of their faith.

- Hinduism: Hindus prostrate before deities, idols, and spiritual teachers as a sign of reverence and devotion. It signifies surrender to the divine and the seeking of blessings.

- Judaism: In Judaism, prostration is practiced during certain prayers and rituals. It symbolizes humility before God and acknowledges His absolute power and authority.

Beyond Religion: Prostration in Socio-Cultural contexts:

Prostration transcends religious boundaries and finds expression in various socio-cultural contexts.

- Ancient Egypt: Pharaohs, considered divine figures, were greeted with prostration, acknowledging their absolute authority.

- Imperial China: Subjects prostrated themselves before the Emperor in a display of complete deference and loyalty.

- Martial Arts: Prostration is often used as a gesture of respect towards instructors and senior students.

- Courts of Law: In some cultures, prostration is still used as a sign of respect and submission before judges and other legal officials.

The Significance of Prostration:

The act of prostration carries immense weight, transcending mere physical action. It embodies:

- Humility: By lowering oneself physically, one acknowledges their own limitations and recognizes the power and authority of a higher being or entity.

- Surrender: Prostration signifies complete submission to a cause, belief, or individual. It reflects a willingness to let go of one’s ego and place one’s trust in something greater than oneself.

- Adoration: Prostration serves as a powerful expression of love, devotion, and reverence towards a deity, spiritual leader, or someone held in high regard.

A Universal Gesture:

Prostration, despite its variations across cultures and contexts, remains a powerful and universal form of human expression. It transcends language, culture, and religion, offering a glimpse into our shared human desire to connect with something greater than ourselves. Through this simple act of lowering oneself, we acknowledge our limitations, surrender to something higher, and express our deepest respect, devotion, and adoration.

Meaning of Prostration in Buddhism

In Buddhism, prostration is a symbolic act of reverence and humility, steeped in deep philosophical and spiritual significance. It is an embodiment of the practitioner’s respect towards Three Jewels: the Buddha (the enlightened one), the Dharma (the teachings), and the Sangha (the community of practitioners).

Prostration, or ‘vandana’ as it is known in the Buddhist context, is traditionally performed by kneeling on the ground, placing the palms together in a position of prayer, and bowing the head and body to the ground. The act symbolizes the practitioner’s surrender to the divine wisdom of the Buddha, acceptance of the teachings of Dharma, and respect towards the Sangha—the community of fellow practitioners.

The act of prostration is not simply an empty gesture; it carries significant symbolic weight in the practitioner’s spiritual journey. In Buddhist philosophy, the ego or self-conception is identified as a source of suffering. Prostration, by embodying the physical lowering of oneself, assists in subverting this egoic conception and fostering a sense of unity with all sentient beings.

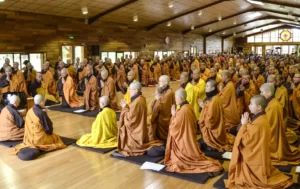

Furthermore, prostration is also interpreted in Theravada Buddhism as an act of ‘making merit’, which is the accumulation of spiritual credits that facilitate progress towards enlightenment. It forms an integral part of daily worship, communal gatherings, and special occasions such as the commemoration of the Buddha’s birth, enlightenment, and death, known as Vesak.

In certain sects of Buddhism, notably Tantric Buddhism, prostrations are even more central to spiritual practice. Prostrations are included as part of ‘ngöndro’ or preliminary practices, where practitioners might perform 100,000 prostrations alongside other forms of devotional acts. The commitment and effort required for such a feat underscore its significance in curbing self-centeredness and developing spiritual discipline.

Overall, prostration in Buddhism is a practice deeply imbued with symbolic, philosophical and devotional elements. Through prostration, practitioners embody the teachings of Buddhism in their everyday lives, nurturing a deeper connection with the Three Jewels and the path towards enlightenment.

Benefits of Prostration in Buddhism

The act of prostration, in Buddhism, transcends its physical form and unveils a treasure trove of benefits for the practitioner. Like a multifaceted jewel, it shines with tangible and intangible rewards, enriching the physical, psychological, and spiritual dimensions of the journey towards enlightenment.

Physical Well-being: Each prostration is a miniaturized yoga session, stretching muscles, increasing flexibility, and strengthening the body. This regular practice becomes a subtle exercise routine, enhancing physical health and cardiovascular fitness. As the body moves with rhythm, blood circulation is stimulated, releasing stress and tension, and leading to a sense of physical and mental well-being.

Mental Tranquility: Prostration becomes a form of moving meditation, cultivating mindfulness and concentration. The repetitive nature of the action, coupled with focus on each movement, helps quieten the mind, calming anxieties and promoting inner peace. This practice becomes a tool for mental training, leading to improved emotional regulation and stress management, allowing the practitioner to face life’s challenges with greater equanimity.

Cultivating Humility: Prostration is a physical manifestation of respect and devotion. By lowering oneself in reverence to the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha, the ego is gently humbled. This act cultivates a sense of gratitude and reverence, reminding the practitioner of their place within the vastness of the universe. It becomes a constant reminder to let go of pride and embrace humility – a cornerstone of Buddhist teachings.

Accumulating Merit: In Buddhist philosophy, prostration is considered a merit-making activity. Each prostration adds to the practitioner’s ‘puñña’, a spiritual credit earned through virtuous deeds. This accumulated merit acts as a catalyst, accelerating their spiritual progress on the path to enlightenment.

Embodying the Dharma: Prostration is not just a ritual, but a physical embodiment of the Buddha’s teachings. Through each bow, the practitioner actively participates in the Dharma, deepening their connection with the teachings and strengthening their commitment to the Buddhist path. This embodied practice enhances their understanding and encourages them to live a life aligned with Buddhist principles.

Spiritual Discipline: In traditions like Tibetan Buddhism, prostration serves as a cornerstone of rigorous spiritual disciplines. Practices involving thousands of prostrations demand significant effort, dedication, and perseverance. By engaging in such challenging practices, the practitioner cultivates mental fortitude, discipline, and resilience – qualities essential for navigating the demanding path towards enlightenment.

Prostration, therefore, becomes more than just a physical act. It is a powerful tool for holistic development, refining the body, mind, and spirit. Through its multifaceted benefits, prostration empowers the practitioner on their journey towards enlightenment, illuminating the path with physical well-being, mental clarity, and unwavering spiritual progress.

The Correct Way of Prostration for Buddhist Practitioners

Prostration, which varies in execution across different Buddhist traditions. However, a generalized form of prostration that is widely recognized in Buddhism can be described as follows:

- Positioning: Stand upright in front of the Buddha statue, Buddhist shrine, or a spiritual teacher, facing towards them. This act symbolizes your intent to engage in a sacred ritual and acknowledges the sanctity of the object or person you are facing.

- Anjali Mudra: Join your palms together at the chest or face level, fingers pointing upwards. This gesture, called ‘anjali mudra’, symbolizes respect and is commonly used in many Asian cultures. In this context, it signifies veneration towards the Three Jewels of Buddhism—Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

- Kneeling and Bowing: Next, kneel down on both knees. Some traditions suggest placing the right knee on the ground first, followed by the left. Once you are kneeling, bow forward until your forehead touches the ground. This act signifies humility and surrender.

- Full Prostration: Extend your hands forward, palms facing down, until your elbows are fully bent, and your hands are next to your head. Your forehead, forearms, knees, and toes should all touch the ground. This posture constitutes a full prostration and represents the letting go of one’s ego.

- Rising and Repeating: After a brief pause, rise back to the kneeling position, bring your palms together again in the ‘anjali mudra’, and then stand up. The prostration is usually performed three times in succession to pay homage to the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha, respectively.

You must to note that the physical act of prostration should be carried out mindfully, with full awareness of the symbolic significance of the movements. The intent and understanding behind the prostration hold as much importance, if not more, as the physical act itself. However, different Buddhist traditions might have variations in the method of prostration, reflecting their unique cultural and historical influences.

The Different Types of Prostration in Buddhism

The act of prostration, a cornerstone of Buddhist practice, transcends a mere physical gesture. It is a multifaceted expression of reverence, surrender, and devotion, unique in its variations across different Buddhist traditions. Each type of prostration, like a brushstroke on a canvas, adds its own shade of meaning and depth to the practitioner’s spiritual journey.

Five-Point Prostration: This ubiquitous prostration, practiced across Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana traditions, embodies complete surrender and humility. Five points of contact with the ground – forehead, two palms, and two knees – symbolize the practitioner’s offering of their entire being to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

Full-Length Prostration: The Tibetan Buddhist tradition incorporates this full-body act of devotion within its rigorous preliminary practices, known as ‘ngöndro’. The practitioner stretches their entire body flat on the ground, symbolizing complete submission to the Dharma and the path towards enlightenment. This prostration, often repeated thousands of times, cultivates discipline, perseverance, and unwavering commitment.

Half-Length Prostration: This variant, prevalent in Theravada Buddhism, offers an alternative to the full-body prostration. Here, the practitioner kneels and bows until their forehead touches the ground, demonstrating respect and humility without fully extending the body. This option caters to individuals with physical limitations or practicing in confined spaces.

Bowing: In Zen Buddhist traditions, the act of prostration takes a more subtle form – the ‘gassho’ bow. Executed while standing or sitting, this gesture involves joining the palms together in front of the heart or face, symbolizing a respectful greeting or offering of gratitude. The practitioner bows their upper body slightly from the hips, reflecting humility and reverence.

Lotus Bud Prostration: This unique prostration, practiced in the Pure Land tradition of Chinese Buddhism, evokes a sense of purity and devotion. The practitioner kneels on the ground, bows until their forehead touches the earth, and raises their hands together in the air, forming a lotus bud. This symbolic gesture reflects the aspiration to unfold one’s inner potential and blossom on the path of spiritual awakening.

These variations in prostration, far from being mere differences in form, represent the rich tapestry of Buddhist practice. Each type, with its distinct features and cultural influences, offers a unique pathway to cultivate humility, devotion, and spiritual progress. By exploring the diverse expressions of prostration, practitioners can deepen their understanding and find the form that resonates most deeply with their individual practice.

The Difference Between Prostration in Buddhism and Other Religions

Prostration is a common ritualistic practice in many religions around the world, and while it carries a similar theme of expressing reverence and humility, the specific symbolism, method, and purpose can vary significantly between religions. In order to understand the differences, let’s examine prostration in Buddhism and compare it to its practice in other prominent religions.

Buddhism: As discussed previously, prostration in Buddhism is a symbolic gesture of reverence towards the Three Jewels—Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. It also serves to cultivate humility, diminish ego, and express commitment to the Dharma. Practitioners perform prostrations as part of daily practice, special rituals and within monastic settings.

Islam: In Islam, prostration, or ‘sajdah’, forms an integral part of the Salat, the obligatory prayer ritual performed five times daily. Muslims prostrate by kneeling and touching their forehead to the ground, expressing absolute submission to Allah. This act also symbolizes equality among all Muslims, as all believers, regardless of social status, prostrate in the same manner.

Christianity: In Christianity, prostration is less commonly practiced by laity but is more prevalent in monastic and liturgical settings. During ordinations, monastic vows, and the Good Friday liturgy, for instance, individuals prostrate fully on the ground as a sign of humility and surrender to God. Unlike Buddhism and Islam, prostration in Christianity is not typically a part of daily devotional practice for most believers.

Hinduism: Prostration in Hinduism, known as ‘dandavat pranam’, involves lying flat on the ground, face downwards, in reverence to a deity, a holy person, or a sacred object. The act symbolizes total surrender to the divine. Similar to Buddhism, Hindu prostration also aims at reducing the ego, but it differs in the specific religious context and the pantheistic theology of Hinduism.

Judaism: In Judaism, full prostration was historically practiced in the Temple in Jerusalem. Today, full prostrations are rare, with most Jews performing a form of bowing during certain prayers instead. During the High Holy Days, particularly on Yom Kippur, some Jews practice full prostration, laying face down on the ground in repentance and seeking atonement.

These comparisons demonstrate that while prostration as a physical act of reverence is a common thread in many religions, its specific form, symbolism, and frequency of practice can vary significantly. Each tradition imbues prostration with its unique theological and spiritual interpretations, reflecting its distinct historical, cultural and religious context.